The Pacific Railroad was chartered in Missouri in 1849 to build a railroad from St. Louis to the Pacific Ocean. Due to financing problems and outbreaks of cholera, construction did not begin until 1851 with a groundbreaking at which prominent citizens of St. Louis turned out to celebrate the start of construction of the line. It included speeches, a national salute, and the reading of a poem written for the moment in history. …

Author Archives : Frank Griggs, Jr., Dist. M. ASCE, D. Eng., P.E., P.L.S.

About the author ⁄ Frank Griggs, Jr., Dist. M. ASCE, D. Eng., P.E., P.L.S.

Dr. Frank Griggs, Jr. specializes in the restoration of historic bridges, having restored many 19th Century cast and wrought iron bridges. He is now an Independent Consulting Engineer. (fgriggsjr@twc.com)

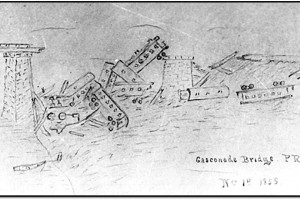

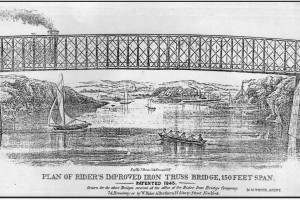

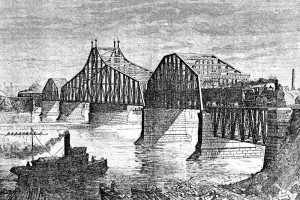

This is the first in a series of articles on bridge failures in the United States. While failures are always newsworthy, especially if there is a loss of life, they are also lessons for bridge engineers to learn from. Failures, while traumatic, can be good teachers. Over the coming issues, this series will describe 20 failures, some of which you may have heard of. The earliest failure was in 1850 and the most recent in 1987. …

Alfred P. Boller’s Thames River Swing Bridge (STRUCTURE, February 2019) remained the longest swing span in the world until J. A. L. Waddell’s Omaha Bridge over the Missouri River in 1893 with its 520-foot span. Waddell would build a bridge in 1903, very similar end-to-end to his 1893 span, with a slightly shorter span. It was not until 1908 that Ralph Modjeski built his Willamette River Swing Bridge in Portland, Oregon, with a 521-foot span and the title of the longest swing bridge was wrested from the Omaha twin swing bridges of Waddell. …

New London, Connecticut, 1889

Alfred P. Boller (STRUCTURE, November 2011) had already designed swing bridges across the Pequannock River, Harlem River, Hudson River, Ft. Point Channel, and the Arthurkill when he was called to be the designer of the longest swing bridge in the United States across the Thames River in Connecticut. …

After graduating from the University of Cincinnati in 1892, Joseph Strauss (STRUCTURE, October 2012) became a draftsman for the New Jersey Steel and Iron Company at Trenton, NJ. At the end of the year, Joseph went to the Lassig Bridge and Iron Company of Chicago for two years, working as a detailer, inspector, estimator, and designer. …

In 1893, John A. L. Waddell (see bio in STRUCTURE, February 2007) designed, based on the designs of Squire Whipple, a lift bridge over the south branch of the Chicago River at South Halsted Street. Plans were made to replace a damaged swing bridge at the site with another swing bridge but the “lake navigation interests” objected, arguing that the old bridge was “always a serious obstruction to navigation.” Their argument was heard by the Corps of Engineers who ruled that they “would not permit him [the Commissioner of Public Works Aldrich] to build any structure which would narrow the water-way to such an extent as would a rotating draw span.” …

Utica, New York 1873

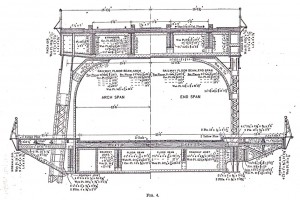

The Hotel Street Lift Bridge, constructed in Utica, New York, in 1873, was a first of its kind and a gateway to long-span lift bridges in later years. In the 1850s, the Erie Canal Board adopted Whipple bowstring trusses (STRUCTURE, January 2015) to cross the canal in cities requiring a span of 72 feet, as that was the standard span for the Whipple bowstring. …

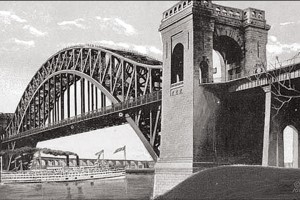

Gustav Lindenthal was chief engineer of the New York Connecting Railroad for many years. The length of his section was 3.38 miles long and extended from a point in the Bronx at the intersection with the New Haven Railroad to Stemler Street in Long Island City. The line from north to south crossed the Bronx Kill, ran over Randall’s Island, across the Little Hell Gate, across Wards Island and over the East River at Hell Gate, and then by a long viaduct to the southerly-most point of his Division. The largest of the three bridges on the line was the Hell Gate. …

Over the years, Leffert Buck (STRUCTURE, December 2010) replaced some of the wires, added anchorages, replaced the wood and iron suspended span, and finally changed the masonry towers with iron in Roebling’s Niagra Suspension Bridge (STRUCTURE, June 2016). The bridge, with its single track, outlived its usefulness by the early 1890s. Buck received the commission to build a new two-track bridge on the same alignment without interrupting traffic. His assistant in the calculations and his resident Engineer was Richard S. Buck, graduate from Rensselaer in 1887. The two Bucks would have an association lasting twenty years. …

Samuel Keefer’s suspension bridge that opened in 1868 just below the Falls of Niagara was replaced by the Niagara-Clifton Steel Arch Bridge. Leffert L. Buck (STRUCTURE, December 2010) replaced Keefer’s wooden towers with iron and later replaced and widened the wooden suspended structure with iron in 1888. …