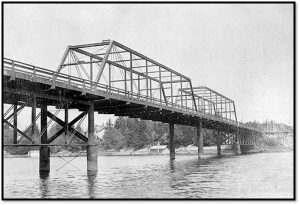

The Point Ellice Bridge crossed the Upper Harbor from Victoria, British Columbia, to Esquimalt. The first wooden pile bridge at the site was built in 1861 and was replaced in 1872. This was replaced by an iron bridge built in 1885 by the San Francisco Bridge Company for regular carriage, wagon, and pedestrian traffic. It was turned over to the City of Victoria by the Provincial Government in 1891. Engineering News described the bridge:

“It consisted of two 120-foot deck spans of Pratt combination trusses, 15 feet deep, with panels 17 feet 6 inches long; two 150-foot through spans of Whipple combination trusses, 25 feet deep, with eight panels 18 feet 9 inches long; and a short trestle approach…The piers were pairs of iron cylinders filled with concrete. The trusses were 20 feet apart, center to center, carrying a roadway 19 feet wide in the clear, with felloe or wheel guards 3 x 6 inches. Two 5-foot sidewalks were added after the bridge was commenced, each having three lines of 2- x 12-inch joists and 2- x 12-inch floor planks. The floor was about 20 feet above the water.”

Even though the trusses were iron, the entire deck was wood. Crossbeams on the 150-foot spans were 12 ×18 inches with wooden stringers. They were hung from the trusses with 1⅛-inch bars passing through the ends of the beams.

In 1889, The Victoria Tramway Company, later the Consolidated Electric Railway Company, obtained a charter to use the bridge for their streetcars, possibly without checking to see if the bridge was strong enough for additional loading. When the San Francisco Bridge Company heard of this, they visited the bridge. They determined the bridge was not designed for that loading, as they had used a static load of 600 pounds per foot and a rolling load of 1,000 pounds per foot in their design. However, they were told by the engineer of the Tramway Company that he had checked, and the bridge was safe. Initially, the Tramway Company had simply spiked iron straps to the planks and placed them close to one side of the bridge with a clearance at the outer rail of 2 feet 7 inches and a gauge of 5 feet. They added no additional stringers.

In 1893, one of the cross beams broke under their heaviest car, No. 16, and the deck sagged at the breakage. The city hired a local carpenter/blacksmith to repair the bridge. He replaced five of the seven beams with new 12- × 16-inch crossbeams on each of the 150-foot spans and 1¼-inch hangers with the ends upset to 1⅛ inch. The beams were drilled and notched to receive the bolts, cutting down on the strength of the ends of the beams. He left two existing beams in place, which proved to be penny wise and dollar foolish. At the same time, they replaced the straps with 30# T rails. These rails rested on two 10- × 12-inch stringers that were two panels long with broken joints.

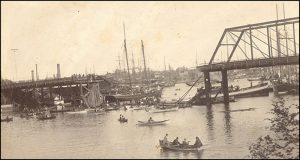

May 26, 1896, was a day of celebration in Victoria, as people were celebrating Queen Victoria’s 76th birthday at a carnival in Esquimalt. The Consolidated Electric Railway Company ran additional cars to handle the number of people attending the festivities. They even brought out car No. 16, their heaviest at 16,000#, to handle the traffic. When the car with a capacity of 60 people, but now carrying 143, crossed the bridge, the span collapsed into the harbor. Evidently, one of the old wooden beams sheared off due to decay and reduced the section, which caused the car to tip side-wards and strike the iron truss work, which then collapsed, leading to the failure of the entire span. The car fell into the water with some of the truss falling behind it. Some of the passengers were killed by the falling ironwork, but most drowned. Of the estimated 143 passengers in the car, 55 died.

A local report stated,

“The central span of Point Ellice bridge had again given way, precipitating the car into the waters of the Arm, where a majority of the imprisoned passengers – men, women, and little children – to whom the world had a moment before been all sunshine, were drowned before aid could reach them. The crashing timbers and ironwork of the bridge piled upon the ill-fated car as the waters received it, and doubling up, pierced it also from below so that many were killed even before the water was reached, while the others were less mercifully held below the muddy waters…So many victims as it claimed that there is scarcely a home in Victoria that has not lost some relative or friend. Ours is a city of desolation and of sadness, and in its mourning, Seattle, Tacoma, New Whatcom, Port Townsend, and the other cities of the Sound are joining, for each has contributed among the holidaymakers who formed the burden of the submerged car some of its well-known citizens.”

A coroner’s inquest was held, and after interviews and investigation by the ten-man jury, found in part,

“That the said accident was the result of the sudden collapse of the eastern Whipple truss of said bridge, and was caused by the weight of car No. 16 of the Consolidated Electric Railway Company and its immense load of passengers, which was in excess of the capacity of the bridge in question as originally constructed, and that the said Consolidated Electric Railway Company is guilty of negligence in not having taken proper precautions for the safe conduct of its passengers accordingly;

That car number 16 was dangerously overloaded with passengers, and in the interest of public safety, it is imperative that restrictions should be imposed upon the traffic of this and similar corporations in the future…

Furthermore, it is manifestly the duty of all corporations of this kind who are entrusted with the safety of human lives to see that all roads and bridges over which it passes are in a safe condition and to take such steps as are necessary to ensure this condition of things being carried on by the proper authorities…

That the bridge in question was adequate in strength to the ordinary traffic for which it was constructed and was under ordinary circumstances suitable for the ordinary railway traffic for which the railway company obtained permission to use it from the government department for whom it was constructed; but the design was poor, the system of construction obsolete, and the contract was not carried out according to specification by the contractors.

We desire to call attention to and to condemn the system of public works which has been, and we believe now is in vogue in the public works department of the city. We find that the city engineer and heads of departments under him who should be held personally responsible for the good and efficient execution of the details of their department are so hampered and interfered with by un-technical, elective superiors that they are without authority necessary to carry out their work, and are consequently without responsibility, which is certainly not conducive to good results…

We find that the specifications call for weldless iron, but that the ironwork in almost all cases were welded, and in many cases of inferior quality, and that the factor of safety provided for in the specifications is of an unknown quantity.

It is quite evident from the evidence produced before us that the primary cause of the accident was the breaking of one certain hanger, shown as number 5 on the diagram produced in evidence, resulting finally in the collapse of the bridge; said hanger being part of the original construction.

We find therefore that the Consolidated Electric Railway Company are primarily responsible for the accident and that the city council is guilty of contributory negligence.” (Victoria Daily Colonist, June 13, 1896, 6)

Engineering News ran a lengthy article on the collapse and wrote in part,

“There are some lessons in this accident which those in responsible charge of bridge structures will do well to profit by. It appears that the bridge in question was built for ordinary highway traffic and was designed to carry a live load of 1,000 pounds per lineal foot. As the combined width of roadway and sidewalks was 31 feet, this was equivalent to a live load of only 32 pounds per square foot, a figure which speaks for itself to any engineer. Manifestly the proper thing to do, if economy was necessary, was to narrow the roadway and sidewalks enough to enable the bridge to carry a crowd without exceeding the load per lineal foot for which it was designed. If a bridge is to be built of a strength suitable for a country highway, then it should be made of a corresponding width; but it is recklessness which cannot be too strongly characterized to make a bridge of a width for a city street and dimension its members as if it were of a width for a highway…

It is not the bridge-building companies who are to blame for this dangerous economy in laying down live loads for structures. Every one of the bridge builders, we venture to say, would much prefer to build structures designed to carry the greatest load that can be placed upon them. Those who are to blame are the designers of structures and those who employ them and insist on a trivial economy at the expense of safety. We are aware that it is hard, oftentimes, for an engineer to stand up for what he knows is good and safe practice. To the average alderman, city councilor, or other layman, it may look like a piece of theoretical nonsense for the city engineer to insist on designing bridges to carry the weight of a crowd which may very probably never come upon the structure. But the only safe rule for the engineer, notwithstanding such opposition, is to stand out for what he knows to be safe and the only safe practice. We believe that the engineer who is in such difficulties may make good use of the descriptions of such accidents as that at Victoria, in this journal, to show to those who oppose him the results which may follow a neglect of sound engineering principles with respect to bridgework.

The second point deserving attention, with respect to the Victoria bridge, is that although it was only designed for a live load of 1,000 pounds per lineal foot, several years after its erection, an electric car line was allowed to lay its tracks across the bridge, and no investigation, or at least no adequate investigation, was made to see whether the structure was strong enough to take the added load…

Another point which may be noticed in this connection is the extent to which the overcrowding of cars is permitted on our street railways, and this has been a direct or indirect cause of many accidents, and the cause of much injury in many accidents not attributable in any way to overcrowding. The companies make little or no attempt to check this, or even to provide additional men in charge of the crowded cars, and some of them (whose roads carry enormous crowds of people) make the absurd claim that if the number of persons in the car was limited to its proper number or if they provided extra men, the profits would be so reduced that the company would have to go out of business. Such a claim cannot be seriously considered. In the accident at Victoria, noted above, about 140 persons were crowded in and upon a car seating only 60. Filling the standing room on days of exceptional traffic is permissible, according to universal American practice. But crowding passengers in cars without limit is barbarous and ought to be prevented by city authorities.” (Engineering News, June 18, 1896, 394)

Court cases of the families of the killed ran on throughout 1897 and 1898 in the Supreme Court of British Columbia. The cases were finally settled in the Privy Council in June 1899 when the Railway was found liable for the deaths.

In summary, the cause of the failure was likely the compounding of bad design, bad construction, lax inspection, and inadequate oversight of the electric railway operation.■