By Robert K. Dowell, Gulen Ozkula, Jui-Liang Lin, Tunc Deniz Uludag, and Ayse Hortacsu

A team of structural engineers investigated the aftermath of the Mw 7.8 and Mw 7.5 Türkiye (Turkey) earthquakes of February 6, 2023.

On February 6, 2023, back-to-back Mw 7.8 and Mw 7.5 earthquakes struck southern Türkiye (Turkey). They caused complete collapse or significant damage to buildings, mosques, churches, industrial buildings, silos, and bridges. Worse, the collapse of tens of 1,000s of residential buildings killed at least 50,000 people. These coupled events caused widespread damage in southern Türkiye and northern Syria, resulting in the most severe earthquake disaster in Türkiye’s history and, potentially, one of the most devastating events globally in terms of substantial loss of life, the collapse and subsequent demolition of tens of thousands of buildings, displacement of a large population, and the significant financial burden. This caused severe disruption over the large area, affecting (1) people’s lives who lost their homes, (2) the economy, and (3) education, with a total of about 15 million people in the affected regions of southern Türkiye. The Mw 7.8 earthquake is of similar size (moment magnitude) to the famous 1906 San Francisco earthquake and what the media and people in general often refer to as the future “Big One” in California, both on the San Andreas fault. This Mw 7.8 earthquake is approximately equal to a magnitude 8.1 event on the old Richter scale.

Undoubtedly, an event of such magnitude as the two earthquakes of February 6, 2023, in southern Türkiye would attract significant international attention, with in-depth investigations to comprehend the deficiencies observed in Türkiye and a reevaluation of both design codes and approaches, especially given that Türkiye has modern seismic design specifications comparable to those used in the United States and the West. In the aftermath of this earthquake disaster, conducting a comprehensive review of the existing design standards and practices is essential, focusing on identifying areas for improvement and implementing revised protocols. The international community recognizes the critical importance of collectively acquiring knowledge from this event, ensuring that invaluable insights are seamlessly incorporated into future design strategies to bolster seismic resilience and effectively mitigate the global impact of similar earthquakes. Consequently, local and international reconnaissance teams collaborated and shared information immediately after the incident, enabling the development of comprehensive reconnaissance action plans while ensuring a cohesive and coordinated approach without interrupting ongoing rescue operations.

This article focuses on the formation of our structural engineering reconnaissance team, who we are, what we did, what types of structures we investigated, where we traveled, who we talked to, and what was said. While this is not a technical article, we have published two technical reports, a technical journal paper, and a technical article documenting observed failed and damaged structures.

Gulen Ozkula, our team leader, communicated effectively with Turkish government authorities with whom she had collaborated during the previous Izmir (Aegean Sea) earthquake reconnaissance in 2020. Gulen conducted email correspondence with the National Science Foundation (NSF) RAPID program to explore proposal options for the reconnaissance team. She also established contact with the highly-regarded seismic organizations of the Earthquake Engineering Research Institute (EERI) and the Structural Extreme Events Reconnaissance (StEER) network to foster collaboration and knowledge sharing in the field, which led to the publication of our reconnaissance report in the EERI Clearinghouse. This report is on the EERI Clearinghouse website. Note that this published report includes input from two reconnaissance teams: the core group of our structural engineering reconnaissance team and the geotechnical reconnaissance team, led by Tugce Baser, an Assistant Professor at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Gulen established connections with local reconnaissance teams to obtain pertinent information from the field, allowing our team to determine priority areas that warranted visits and find the optimal timing for the U.S. team to travel to the different hazard regions. This collaborative communication network facilitated informed decision-making and strategic planning for our reconnaissance efforts.

Structural Engineering Reconnaissance Team (Mountain Goats)

Due to the earthquake’s considerable magnitude and widespread impact in southern Türkiye, meticulous planning was imperative in determining the reconnaissance route, duration of the mission, and team composition. Considering her field experience and proficiency as a native speaker originally from Türkiye, Gulen Ozkula, an Assistant Professor at the University of Wisconsin, Platteville, assumed the role of coordinating the entire expedition and establishing local connections. With the reconnaissance route and duration finalized, a diverse team comprised of experts from various disciplines was assembled to ensure comprehensive coverage. In addition to team leader Ozkula, team members include Robert K. Dowell, a structural engineering professor at San Diego State University (SDSU) and Director of the SDSU Structural Engineering Laboratory; Tunc Deniz Uludag, a structural engineer at Martin/Martin Inc. in the U.S., and originally from Türkiye; Ayse Hortacsu, a structural engineer and Director of Projects at the Applied Technology Council (ATC) in the U.S., also originally from Türkiye; and Jui-Liang Lin who is a structural engineer and Research Fellow, as well as Division Director for the Building Engineering Division of the National Center for Research on Earthquake Engineering (NCREE) in Taiwan, another location that had a major and well-known earthquake from 1999.

On the first day in the field, the team came upon the large Nurdagi Viaduct and parked to take a closer look without any prior notice that the bridge was damaged. Uludag was the first to see the plastic hinge formed part way up the large 10-foot-diameter reinforced concrete (RC) column, resulting in Dowell and Uludag descending the long distance down to the bridge’s foundations. At the same time, the remaining team members stayed at the top of the structure, next to the adjacent roadway we came in on. Observing how Dowell and Uludag moved down the steep dirt embankments and jumped multiple obstacles to the bottom of the bridge, Hortacsu gave our team the name Mountain Goats, and it stuck! We were in the low mountains of southern Türkiye at the time, where the Nurdagi Viaduct is. On a subsequent trip to Türkiye, Dowell confirmed that all columns are being retrofitted with steel jackets at an in-person meeting in Ankara with the design engineer responsible for the seismic retrofit of this viaduct. He also met with engineers at the Turkish Highway Authority, including the Chief Bridge Engineer for Türkiye. Overall, the transportation network performed well and was fully operational within three days of the earthquakes. This is in stark contrast to the residential construction that suffered 1,000s of collapsed buildings and was responsible for most, if not all, of the deaths in this disaster.

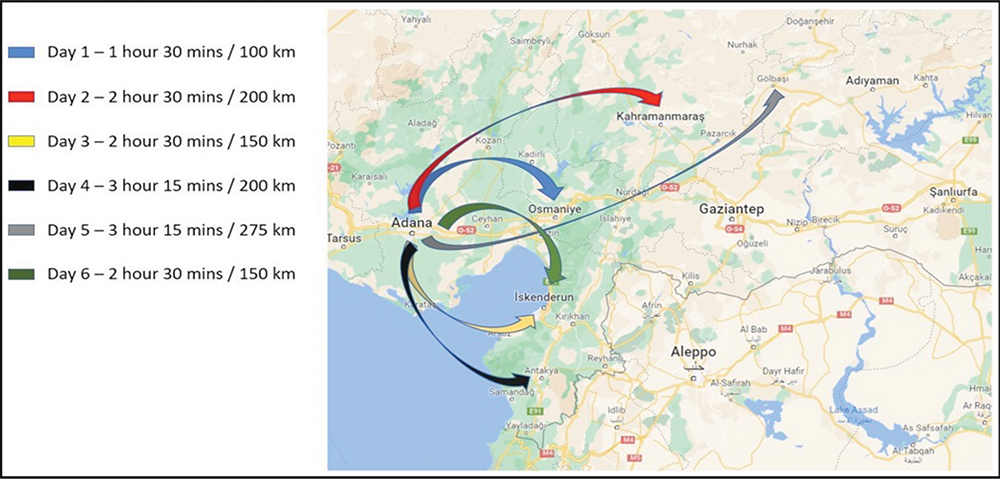

The team arrived in Adana, southern Türkiye, on February 19, two weeks after the two earthquakes, and met for the first time on the morning of the 20th for breakfast at the lobby of Hotel Ibis. This date was selected as the first day for the field because it was the day after search and rescue efforts were stopped and before most of the damaged and failed structures were demolished and removed, or changed in any way. Adana would be our base for the full time we were in southern Türkiye, leaving in the morning to the most affected areas and returning each evening.

Daily Routines to the Field and Back to Our Base in Adana

Earthquake reconnaissance efforts presented considerable challenges. Assessing the aftermath of a major earthquake entails confronting the distressing realities of extensive devastation, loss of life, and human suffering. Furthermore, it involves enduring physically demanding conditions for long hours within a hazardous environment. Ongoing aftershocks, collapsed structures, and unstable ground amplify the risks reconnaissance teams face. Thus, meticulous coordination and careful planning were required before entering the affected zones. One example is wearing masks, which our team often did, not because of COVID-19, but to protect against breathing significant concrete dust and other hazardous materials from the ongoing demolition and removal work in the affected cities. Another considerable risk was driving into areas with multiple collapsed and damaged/leaning buildings, with the road width narrowed, and having to drive very close to and around unstable structures that could fall or topple further at any time, especially in an aftershock.

Given the profound devastation within the hazard zones and the long daily drives from Adana to the different regions of interest, securing a vehicle and driver was essential to facilitate the reconnaissance mission. This allowed our team the flexibility to stop at any time (even when no parking was available since the driver could drop us off, leave, and pick us up when we were done) and closely examine intriguing structures encountered along the way, especially ones that we could see as we were driving along had fallen over or were severely damaged. With this capability, we could thoroughly investigate sites of interest to enhance our understanding of the earthquake’s impact. In the mornings, we would meet for breakfast at about 7 a.m. or 7:30 a.m. at the hotel lobby, then sit together to eat and talk before going up to our rooms to gather what we needed for the day in the field, then meet again outside the hotel in the van by about 8 a.m. Each day, we traveled to different affected cities or regions and returned in the evening, with drive times each way of between one and three hours. This went on for six days in a row. While looking at structures in the field only in sunlight, we often returned to Adana after dark due to the long drive times. We ate dinner together each evening in Adana.

Places Visited

The Mountain Goats visited structures in the most affected cities and regions in southern Türkiye, including Gaziantep, Iskenderun, Osmaniye, Antakya (Antioch), Kahramanmaras, Nurdagi, Golbasi, and Hatay. As the van approached a region that experienced severe shaking, we would typically start seeing damaged and collapsed structures out the window while still driving along in our van, such as farmhouses and various other structures in rural areas. Often, we would see something of interest and ask the driver to stop; then, we would all pile out of the van and walk toward the structure. We visited and looked over the structure for damage, sometimes with permission and other times without, depending on the situation and accessibility of the site. This happened most often with industrial facilities and silos that we could see had toppled. Part of this process was to take a picture of the hand-held Garmin GPS unit that Rob had on his belt, allowing us to figure out later where and what the structure was using the GPS coordinates since we were often stopped in—what felt like—the middle of nowhere.

Communication and Collaboration: Engaging With Locals and Working With Stakeholders

For international researchers, conducting reconnaissance efforts in foreign countries presents several challenges. Cultural and linguistic barriers may hinder communication and comprehension. Local knowledge, resources, and infrastructure constraints can compromise the precision and understanding of assessments. In addition to adapting to diverse institutional frameworks and safety concerns, it is necessary to build networks with local specialists and acquire permission to visit a site or structure, if required. Time constraints and coordination further complicate these endeavors, highlighting the need for proactive planning, collaboration, and cultural awareness to ensure the success of international reconnaissance missions. The Mountain Goats were fortunate to have Hortacsu, Uludag, and Ozkula, all originally from Türkiye and, therefore, native speakers with a deep understanding of the culture and many local connections to help our foreign researchers overcome these obstacles.

It was essential to collaborate with individuals from the local region to overcome the complexities of gaining relevant authorizations and obtaining exact instructions for specific sites. For instance, on the third day in the field, the team visited Ercan Acimis, a local business owner originally from Iskenderun. While at his office, we were served cups of tea while we talked and got information. He told us about the damaged bridge over the Asi River, which became one of two main bridge structures with severe and unusual damage to the team, and other locations and potential structures of interest. He also called various people to get more information and permits based on our questions.

In Nurdagi, Turkish engineer Ibrahim Baran (with the Ministry of Environment and Urbanization), a friend of Uludag’s, came with us in our van, sitting in the front passenger seat to direct our driver where to go, showing us around parts of the city to see various damaged and failed buildings of interest, including some that had properly formed plastic hinges in the frame members. He was responsible for overseeing the demolition and removal of heavily damaged buildings tagged for demolition. As we were standing on the street looking at damaged buildings, a married couple walked up to talk to Baran about their home right next to a severely damaged building marked for demolition. They asked that he bring the building down without affecting their home, which was not damaged. He responded that he would try but could not promise anything.

On the first day in the field, Uludag and Dowell met Hasan, an excavator operator responsible for demolishing a collapsed building. He told us that 104 of the 107 residents of that building had died. Hasan also said that he helped bring the dead out of the building and that they were still on their mattresses, where they had perished from the just-after 4 a.m. earthquake.

Yakup, whose mother was killed in the earthquake, spent considerable time showing team members Uludag and Dowell around his damaged village where the fault rupture from the Mw 7.8 earthquake had come through, with significant surface rupture, subsidence, and lateral spreading in many locations around the village, resulting in splitting one house right down the middle. This tour included walking into people’s homes, their backyards, and alleyways around and through the village. Such access wouldn’t have been possible without Yakup, who was kind enough to spend much time with us and knew all the villagers. The local village people gave us tea, which was much appreciated.

During our reconnaissance tour, we were profoundly touched by the genuine hospitality exhibited by the Turkish people at every step. One team member, Jui-Liang Lin, received special attention and was treated with great reverence. The Turkish people strongly believe that Japanese engineers possess extensive expertise and experience in earthquake engineering, thus garnering immense respect for engineers of Asian descent. Consequently, residents whose homes had sustained varying degrees of damage at almost every location we visited expressed a strong desire for Jui-Liang Lin to conduct further investigations. At many stops, the locals wanted to take pictures with him, and he happily obliged them each time, never letting on that he was actually from Taiwan rather than Japan. Clearly, the input of every expert is invaluable for those significantly affected by this devastating event.

As fellow human beings, we researchers were all emotionally moved by witnessing the hardships faced by the local population and hearing the stories of their lost loved ones. Whenever individuals approached us seeking expert opinions, we endeavored to provide assistance and impart as much information as possible. We aimed to ensure that if their homes had suffered severe damage, they would refrain from reentering until it was deemed safe. It is important to note that unfortunate fatalities occurred due to aftershocks when some individuals ventured into their severely compromised buildings in an attempt to retrieve personal belongings.

Going Through the Largest Aftershock (Mw 6.3) While in Adana, Southern Türkiye

At the end of the first day in the field, the Mountain Goats went to dinner for a classic kebab at a well-known restaurant in Adana called Onur Kebap. The Adana Kebab is known throughout Türkiye, being served in places as far away as Istanbul and in the capital, Ankara, as a specific type of kebab. Although we selected the town of Adana for its central location (distance) to the most heavily damaged cities and regions, while being far enough away where we felt safe from building collapse due to further earthquakes and aftershocks, Adana did suffer more than ten building collapses on February 6 from the large back-to-back earthquakes. When the appetizers were done, and right after the waiter placed Dowell’s first kebab in Türkiye on the table before him, but before his first bite, the two-story building started swaying back and forth from an earthquake. The servers and restaurant staff all had the same shocked look on their faces, pure terror with wide-open eyes, and then they ran for the exit and down the stairs to the safety of the outside, with the rest of us following. They were all suffering from severe trauma due to what they had gone through on February 6, only two weeks earlier.

After the shaking had ended and a few minutes more spent outside, we all made our way back up to the restaurant, where we finished our meals. After messages from family and friends, we turned on the restaurant TV, and learned from national and international news that we had just experienced an Mw 6.3 aftershock, the single largest aftershock of the 1,000s since the big earthquake. Note that this has also been reported as its own earthquake, since it occurred on a different fault than the two earthquakes of February 6. There was also a panicked series of messages from SDSU about Dowell’s well-being, finally relayed back and forth through his daughter, Sophia, that he went through the big aftershock but was all right. Sadly, it collapsed several more buildings in Hatay, killing a few more people there, which was the location of the epicenter. The shaking we felt in Adana was less severe than in Hatay since we were about 70 miles away. When we returned to Hotel Ibis after dinner, people were still milling outside, afraid to go back into the eight-story building after the shaking; the motion was probably significantly amplified over what we felt at the restaurant due to the hotel’s height.

Lessons Learned From the Earthquake Reconnaissance

The extensive damage caused by the two earthquakes of February 6, 2023, resulted in the worst earthquake disaster in Türkiye’s history, with over 50,000 people killed and tens of 1,000s of buildings collapsed or damaged beyond repair. It also left millions homeless, resulting in multiple tent cities across southern Türkiye and over 300,000 destroyed apartments, indicating that the actual death toll may be much higher than the official number of 50,000, which was based on the number of bodies pulled from the rubble of collapsed buildings.

The Türkiye reconnaissance trip allowed us to observe the extent and type of damage caused by the earthquake. Comprising engineering experts in bridge structures and building structures of reinforced concrete and steel, each team member had the opportunity to acquire firsthand knowledge from this devastating seismic event and collect perishable data for potential future proposals to enhance design codes. Furthermore, our engagement with the local community allowed us to gain profound insights into their experiences during the earthquake, encompassing a comprehensive understanding of evacuation procedures, the efficacy of emergency response measures, and the resilience demonstrated by communities in the face of such devastating disasters.

Our team anticipates that international collaboration and research engagement will catalyze advancing seismic design and construction practices in Türkiye. We hope that through this collective effort, we will not only derive valuable insights from this event but also foster the development of resilient structures and communities globally. By leveraging the knowledge gained from studying this earthquake, we hope the civil engineering community will contribute to creating safer and more resilient built environments worldwide. ■

Prof. Robert K. Dowell, Ph. D., P. E., is Associate Professor of Structural Engineering and Director of the Structural Engineering Laboratory at San Diego State University (SDSU). He has over 30 years of experience in bridge design, structural analysis and physical testing to failure in the laboratory. He can be reached at (rdowell@sdsu.edu).

References

Ozkula, G., Baser, T., Dowell, R. K., Hortacsu, A., Huang, C. W., Ilhan, O., Lin, J. L., Numanoglu, O. A., Olgun, G. C., & Uludag, T. D. (2023). Earthquake Reconnaissance Team Report: Türkiye Earthquake Sequence on February 6, 2023. Learning From Earthquakes. https://learningfromearthquakes.org/2023-02-06-nurdagi-turkey/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=80

Dowell, R. K. (2023). Reconnaissance Report of Observed Structural Bridge Damage: Mw 7.8 Turkiye (Turkey) Earthquake of 2023. SDSU Structural Engineering Research Project, Report No. SERP – 23/03, March 2023.

Ozkula, G., Dowell, R.K., Baser, T., Lin, J.L., Numanoglu, O.A., Ilhan, O., Olgun, C.G., Huang, C.W., Uludag, T.D. (2023) Field reconnaissance and observations from the February 6, 2023, Turkey earthquake sequence, Natural Hazards.

Dowell, R. K. (2023). Observed Bridge Damage from the Mw 7.8 Türkiye (Turkey) Earthquake of February 6, 2023, STRUCTURE Magazine, October Issue, 2023.