The story of the Sloss Furnace Company is more than a story about a historic manufacturing plant. Like most structures, the iron-producing furnaces were built to generate income for the owners by filling a product need produced at a competitive price that utilized locally available raw materials and human capital.

The Sloss Furnace Company also fits into the larger economic development framework of the post-Civil War South within a timeline that runs from before the Civil War through the early 1920s when poorer Southerners, including many formerly enslaved people or their descendants, moved North in search of better opportunities, through the 1950s.

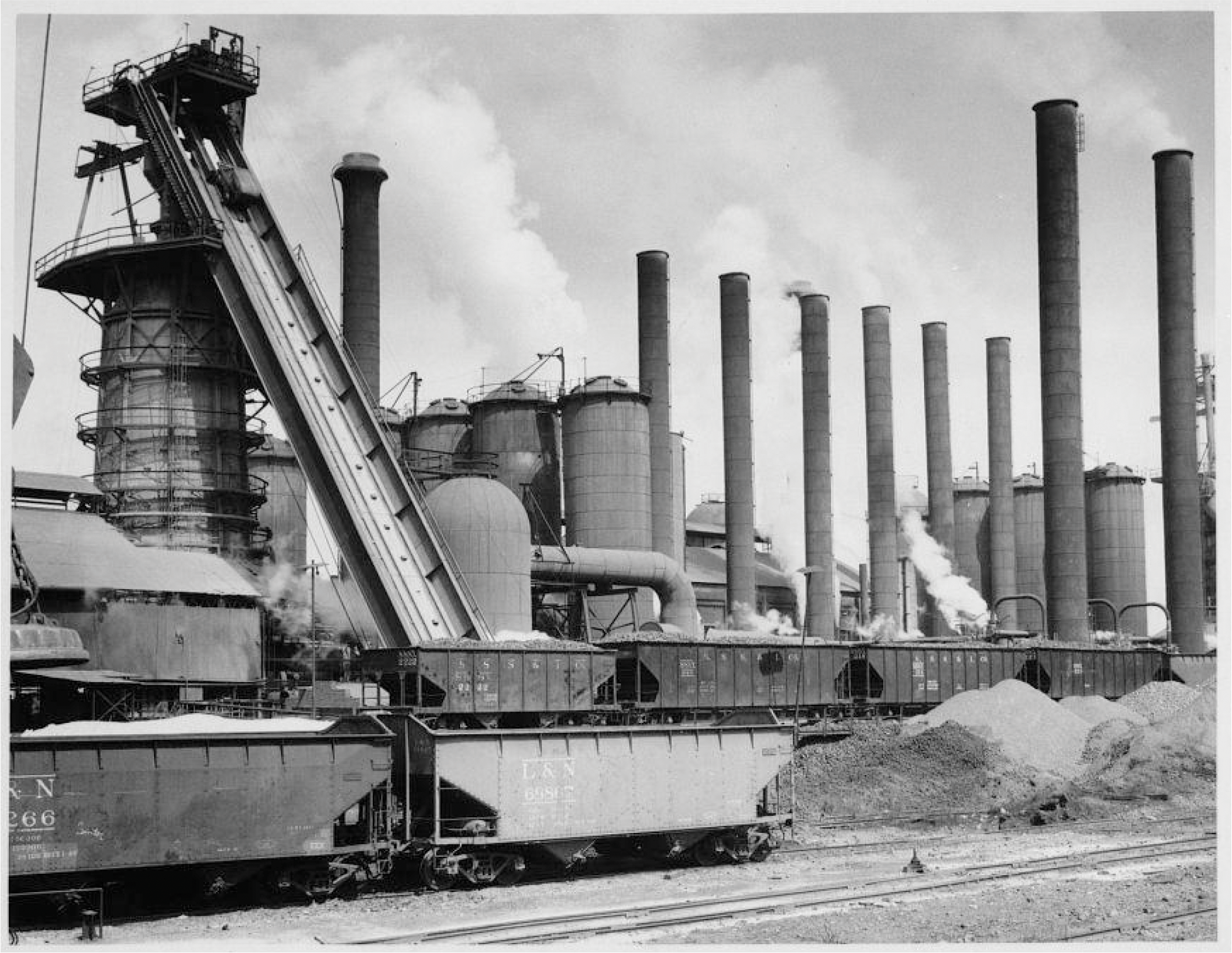

The furnace complex is the oldest remaining blast furnace site in the Birmingham Iron and Steel District (Figure 1). The furnaces are prime examples of post-war efforts to rebuild and industrialize the largely agrarian South after the Civil War, during which history has shown that the more industrialized North had a distinct manufacturing advantage.

It is also a story of the City of Birmingham, Alabama, which was founded in 1871, taking its name from Birmingham, England, one of England’s major industrial cities at the time. Due to a unique combination of available raw materials within a 30-mile radius, this part of central Alabama grew into a major industrial center focusing on the iron and steel industry. Birmingham also became a major railroad crossroads, allowing for the export of finished products to distant markets. The iron and steel industry in the Birmingham District became the leading iron and steel-making center in the South (overtaking Tennessee), competing with its chief Northern rivals, principally the mills located in and around Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Besides supplying domestic markets, the Birmingham plants also exported large amounts of pig iron to foreign markets starting in the 1890s, competing with Middlesbrough, England, and Glasgow, Scotland.

Overview of Southern Iron and Steel Production

Iron production in the South dates to the 1790s. At that time, the production was on a small, local basis, with blacksmiths and mechanics operating foundries and forges in a number of locations throughout Georgia, Tennessee, and the Carolinas. The main product was wrought iron (a form of steel) that could be turned into tools and other metal implements. The region, however, made little progress compared to the North in building larger-scale production prior to the Civil War. In 1860, the South was producing only about 25% percent of the nation’s bar, sheet, and railroad iron and less than 10% of its pig iron. The war spurred a boom in Southern iron production, as much-needed gun forging works and arsenals were erected throughout the region to supply the war effort.

The Red Mountain Iron Company built its famous Oxmoor plant near Birmingham in 1862. The plant, located along Shades Creek in the Oxmoor Valley of the Birmingham Industrial District, was the first to make use of Alabama’s red hematite ore in significant quantities and helped establish the pig iron industry in the area. The iron ore was mined from Red Mountain, a southwest-to-northeast ridge located to the south of Birmingham. The Oxmoor plant, as well as the Irondale and Tannehill furnaces, were destroyed by Federal troops near the war’s end as the Northern Army marched southward. After the war, southerners revived and rebuilt the iron industry, and it eventually became an important part of the industrialized “New South.”

Sloss Furnace Company

The Sloss Furnace Company was the creation of James Withers Sloss. Sloss was born on April 7, 1820, of Scotch-Irish descent in Mooresville, Alabama, located roughly 80 miles north of Birmingham. He was a second-generation American, his father having emigrated from County Derry, Ireland, in 1803.

Sloss appears to have received little formal education, but at the age of 15 was able to land a job as an apprentice bookkeeper for the local butcher. After the traditional seven years of apprenticeship, he was able to purchase his own store in Athens, Alabama. He also ran his own plantation and served as a Colonel in the Confederate Army.

After the war, he became involved in the railroad industry and started working alongside the noted Alabama industrialist Daniel Pratt (1799-1873) at the rebuilt Red Mountain Iron Company’s Oxmoor Furnaces. Following success there, Sloss joined Truman Aldrich and Henry Fairchild DeBardeleben in establishing the Pratt Coal and Coke Company located in Birmingham, suppliers of coal and coke to the local furnaces.

Sloss started his own firm, the Sloss Furnace Company (hereafter referred to as Sloss Furnaces or Sloss), in 1881 after leaving his partnership with DeBardeleben and Aldrich. He engaged Harry Hargreaves, a Swiss-English engineer, to supervise the construction of two blast furnaces. The first furnace went into operation (“blew in” in industry parlance) in 1882, and the second in 1884. The ovens of the original Sloss furnaces were designed by the English inventor Thomas Whitwell, who first introduced his “stoves” into the U.S. in the 1870s. Hargreaves, an acquaintance of Whitwell, brought them to use at Sloss. Pig iron (an intermediate product in the production of steel with a high carbon content of 5% to 6%) was the main product of the Sloss Furnaces. In its first year of operation, the Sloss Furnaces produced 24,000 tons of pig iron, producing the product at a cost of about $8 per ton less relative to a total cost between $15 and $20 a ton at the Northern plants.

The iron ore for the Sloss Furnaces was extracted from company-owned mines, Sloss #1 and Sloss #2, located on 40 acres of land on the south side of Red Mountain, roughly 10 miles southwest of the furnaces. Red Mountain is a southwest-to-northeast trending ridge and the southernmost tail of the Appalachian Mountains. The remaining mines and mine buildings, including some equipment, are preserved in Red Mountain Park. Coal/coke, limestone/dolomite, and other ingredients were supplied from other non-company mines located throughout the Birmingham area.

The Basics of Pig Iron Production

The raw materials needed for pig iron production are iron ore, coke (processed coal), and limestone/dolomite. Pure iron does exist naturally in the Earth’s crust, but is bound up in iron oxide-containing rock. Coke is the fuel that is made by heating coal until impurities are burnt away and it becomes nearly pure carbon. Limestone/dolomite serves as a flux, helps remove impurities, and is a necessary source of calcium carbonate in the production process. It takes roughly three tons of red hematite ore and 2,500 pounds of coke to make one ton of pig iron.

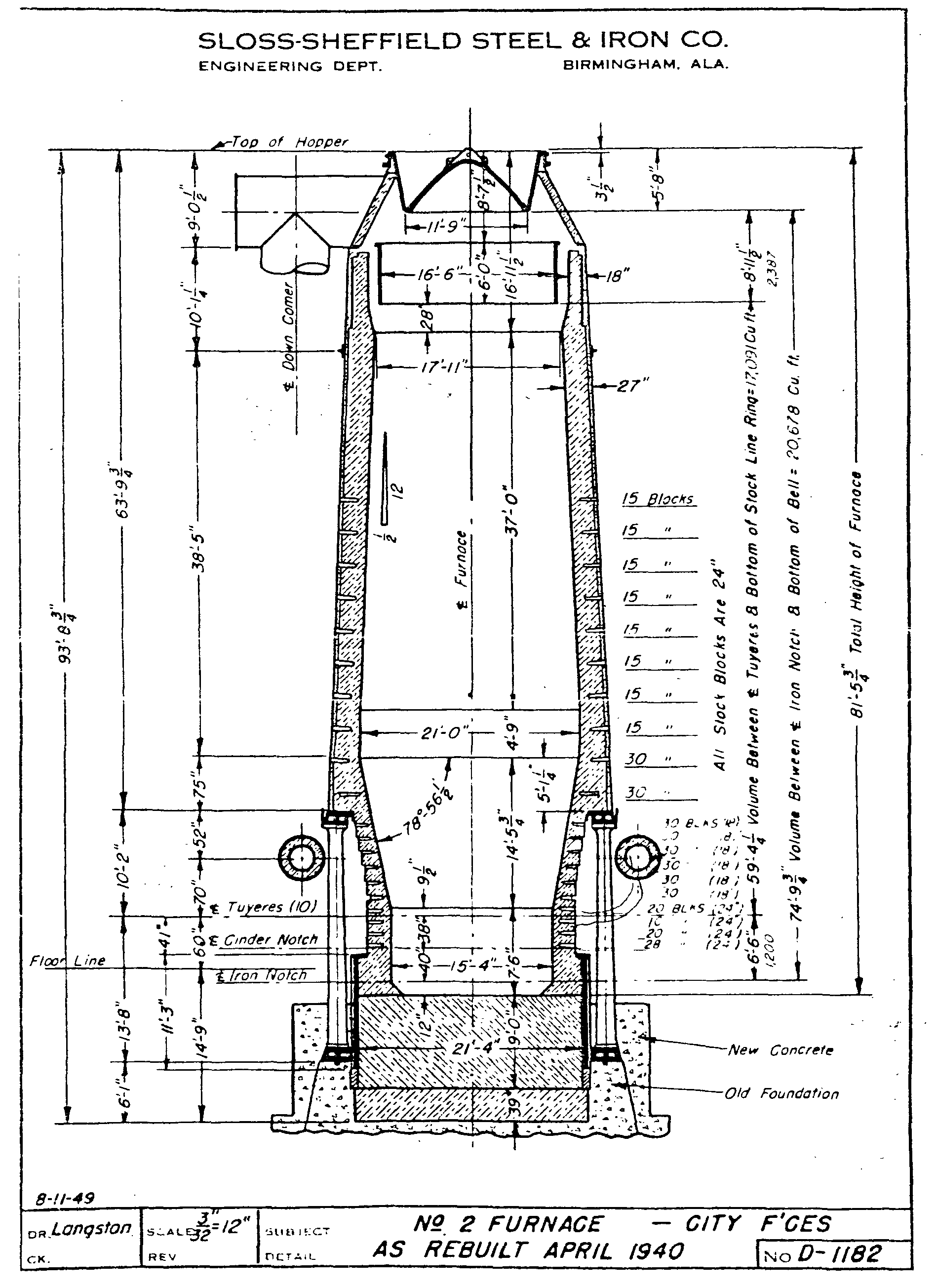

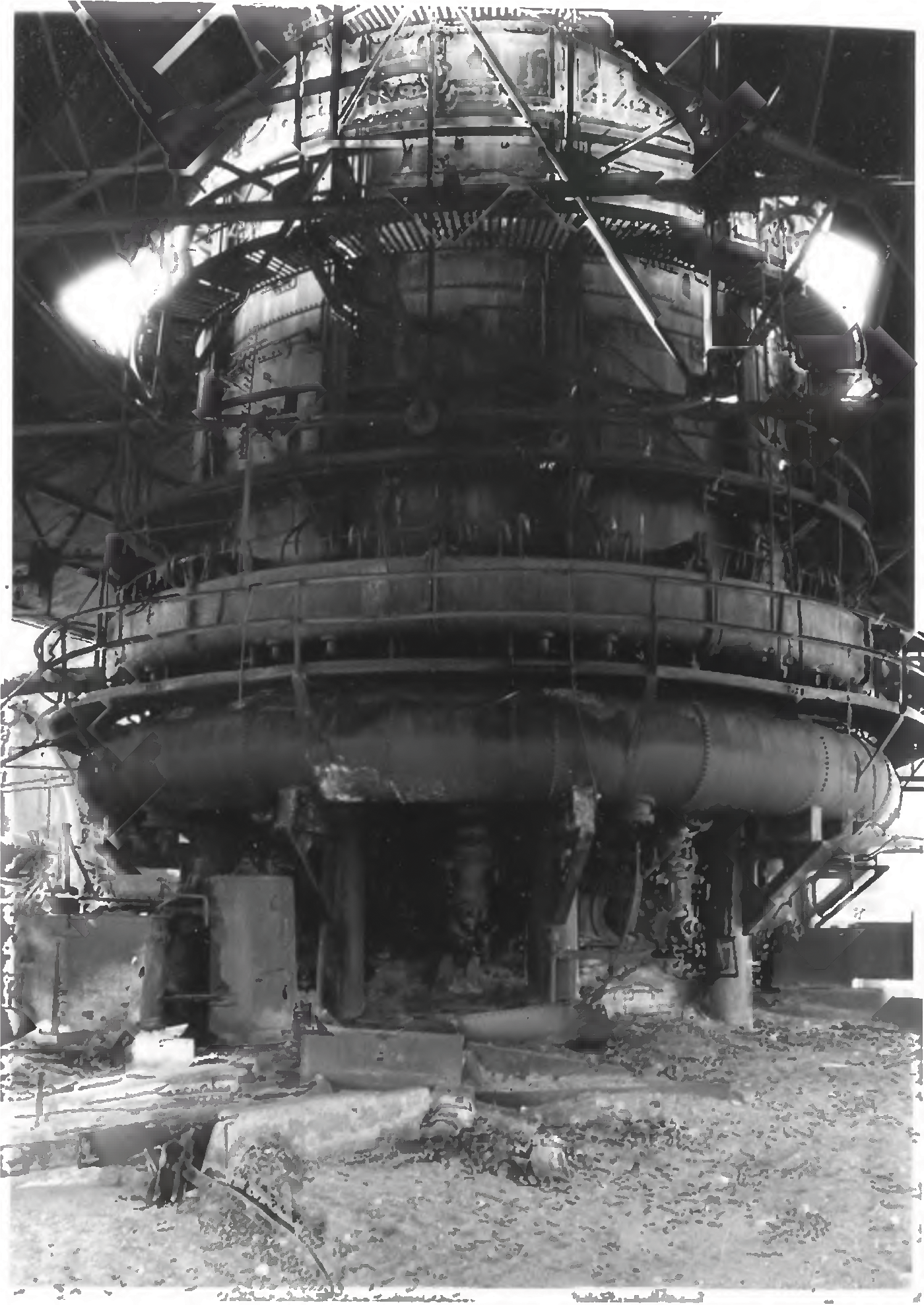

A blast furnace is essentially a tall hollow steel tower (perhaps better described as a tank, vessel, or caldron) that serves as a container for the smelting of iron. The original furnaces at Sloss were approximately 60 feet tall and 18 feet in diameter, lined with heat-resistant, refractory brick. See Figure 2 for a cross-section and Figure 3 for the base of a Sloss furnace.

At Sloss, the raw materials were lifted by elevator from supply bins located on the ground to raised filling platforms and then fed by hand into the top of the furnace. Simultaneously, very hot air (1,600 F) is created in tall cylindrical boilers (see Figure 4), dried, and then injected under pressure through nozzles at the base into the raw material mixture. The coke burns when the injected oxygen combines with the carbon in the coke, forming carbon monoxide. The carbon monoxide reacts with the iron oxides to form iron and carbon dioxide as a byproduct. The “pure” iron sinks to the bottom of the furnace (due to its greater density), while the lighter byproducts of the process, a material called slag, floats to the top. Both the molten iron and the slag are then drawn off independently. Then, more fuel is added, and the process continues.

At Sloss, there were two furnaces, and the “hot metal” from each was transported into large adjoining casting sheds where the liquid iron was funneled through channels on the ground into sand-lined forms to create “pigs,” each weighing around 110 lbs. Once cool, the pigs were removed from the forms by hand and then hand-carried by workers to the nearby train platforms of the Louisville and Nashville Railroad and the Alabama Great Southern Railroad for shipping. The slag, which is a waste product that was historically of no value, is used today as a replacement for Portland cement in concrete. The local ore generated twice as much waste slag as the Northern plants, representing a cost disadvantage. To the extent possible, the exhaust gases were collected in tanks and fed back into the process.

As one might expect in these pre-OSHA days, the work was quite dangerous since, in addition to the high temperatures and exposed conditions, the workers on the filling platforms were inadvertently breathing exhaust gases rising up and escaping through the throats of the furnaces.

The pig iron-making process is a continuous one that runs day and night until the furnace needs to be shut down for lack of raw materials or maintenance, which may include the re-building of the insulating refractory brick. During the early years of operation, and actually well into the 20th century, daily production at the Sloss was around 100 tons of iron per day. This production was much lower than other mills, particularly those in the Northern states, and was largely the result of a labor-intensive operation designed around the use of local, largely untrained, African-American workers rather than a highly mechanized one.

As noted above, Sloss had a major cost advantage over its Northern competitors due to the local labor market conditions. But Sloss, who had no formal experience or training in running an efficient manufacturing operation, found it challenging to run his furnaces and to maintain his workforce. He found the local white population disdainful of manual labor and “imported” white workers who flocked to the Birmingham area unruly and undependable. In the segregated South, it was also difficult to mix the white and black workers. He, therefore, depended on a plantation model employing unskilled formerly enslaved people. He apparently paid a good wage, $1.50 a day, although Sloss soon discovered that good wages alone were not enough to retain workers and to have them report for work on Monday mornings. His solution was to construct company tenement housing (which remained until the 1950s) and company stores to attract what he believed were more reliable married workers. After paying for housing and food, Sloss figured that nearly half of wages ($15 to $20 per month) could be saved. In its heyday, Sloss employed approximately 600 African-American workers.

Pig iron is later processed by melting and exposure to blasting of air to oxidize and remove the impurities (the extra carbon), and then made into steel products. The furnaces in the Birmingham area were hampered by the high phosphorus and silica content of the locally available iron ore. To combat this disadvantage, Sloss employed the latest industry developments and retained the services of expert metallurgists such as Edward Uehling and James Pickering Dovel. Despite these efforts, the economical production of steel from the local pig iron remained beyond his grasp. Therefore, plants like Sloss focused on the production of pig iron, although later, some plants, but not Sloss, also produced cast-iron pipe and pipe fittings. Other common uses of cast iron included such products as cooking skillets, kitchen stove plates, and automobile engine blocks.

The Later Years

Like any commodity produced to a widely accepted standard, price is almost always a prime factor in purchasing decisions, and competition can be fierce. Distinguished scholar C. Vann Woodward has noted that “during the depression of 1884 and 1885, Southern iron made its first successful invasion … into the Northeastern market. This precipitated a hard-fought struggle for sectional dominance in the iron industry that was almost as much discussed as that between Northern and Southern cotton mills.”

James Sloss retired in 1886 at the age of 66 and sold the company to local businessmen. With help from Wall Street financiers, the firm was reorganized and re-named the Sloss Iron and Steel Company. Sloss died in 1890. Following the depression of 1893 and the boom in 1898 resulting from the Spanish-American War, the company expanded and was once again re-organized, this time as the Sloss-Sheffield Steel and Iron Company.

In the late 1920s, the owners were forced to modernize and re-design the 1890s-era technology of the plant as a result of several factors, including competition from the North, “unfair” government-controlled transportation pricing system for Southern iron, and an exodus of African American workers to the North in search of a better life. The plant was eventually sold in 1952 to the United States Pipe and Foundry Company, which continued operations until it was closed for good in 1970.

None of the original furnaces remain today. Yet what does remain dates from the early part of the 20th century and stands today as a fine example of the iron and steel technology from a bygone era; it is preserved in the Sloss Furnaces National Historic Landmark, dedicated in 1981, located just east of downtown Birmingham.■