Survey findings offer insight to potentially mitigate claim risk. Part 2

In our previous article in the June 2023 issue of Structure, we discussed two emerging claims trends identified in the WTW A&E Professional Liability Carrier Survey Report, social inflation and cyber liability. In this issue, we will continue by addressing the impacts of climate change, Covid-19, and risk-shifting in contracts.

Climate Change

Climate change is the one emerging risk that nearly every one of our carriers has on their list. The insurance industry firmly believes in climate change, and there’s a lot to think about regarding the exposures facing design professionals. Current codes are based on what we consider to be a faulty assumption: weather conditions will remain static. Recent changes in weather patterns have led to damage claims resulting from too much water (flooding) and insufficient water (wildfire). Drought conditions have also caused ground desiccation, destabilizing building foundations. Even when the design professional met all applicable codes, we have seen claims that the design professional should have anticipated the extreme event and planned for it.

This is especially true about flooding. Flood is not covered under most standard property policies. Flood insurance is primarily a stand-alone policy from the National Flood Insurance Program administered by The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). Many home and business owners do not buy flood insurance, so they must sue someone else on a liability theory if they suffer a flood loss. And seeing as most municipalities have sovereign immunity, the only parties left to sue are contractors and design professionals who worked on the grading and sewers.

This raises the question: what is the standard of care, and how will that adapt to the new reality of increased frequency and severity of storms? We recommend that clients be presented with options ranging from mere compliance with codes to an adaptive and resilient design. And we want to encourage the client to give more value to the adaptive and resilient design by asking them to look at the cost of it over the life cycle of the building instead of a three- or five-year window return on investment.

The desired result is to cause the owner to place more value on an adaptive and resilient design. But, if we make that offering and document that they declined that offering of a higher level of service to design a better, more resilient structure, then if it is damaged in a flood, a windstorm, or a wildfire, we have a defense. We explained the risks to you, and you decided to accept that risk in exchange for saving money. It is “I told you so.”

The legal concept that we want to obtain is the owner’s informed consent. We want to show them the options and explain the risks of merely complying with current codes. And if the owner elects to do the cheaper thing, to save money by implementing the less adaptive and resilient design, then we have transferred the risk of failure to them under the concept of informed consent.

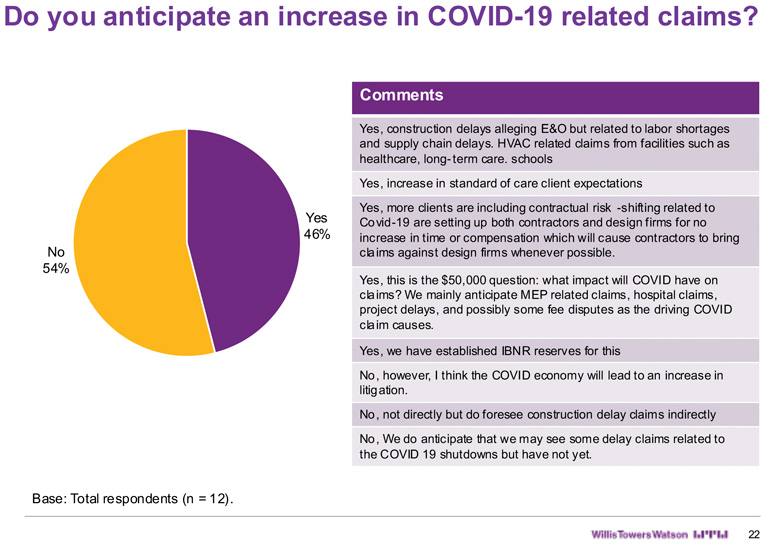

COVID 19

When COVID hit, we wondered what was going to be the impact on design professionals. Initially, we thought it might affect the standard of care by requiring the participation of doctors or other medical professionals in assisting us in the design to try and prevent the spread of viruses. With the development of vaccines, attention has shifted away from disease prevention to the economic impacts of supply chain interruption. Long-tail items are taking even longer to order and obtain, with the result that changes to a design that can lead to delays in completing a project. Some firms are adapting by ordering long-tail items earlier than we would have done historically. This suggests an increased value associated with pre-construction services. We predict that this will become even more valuable shortly, both as a proactive service to the client and as a defensive procedure for design professionals.

This again goes back to the concept of informed consent. Explain to the owner that long-lead systems can only change with a risk of substantial delay. So, we need to think very carefully about the program and understand that it will delay the project and cause additional expenses to make changes. So we want to get owner approval of major purchase decisions in writing.

To make those informed decisions earlier, meeting with the owner, the contractor, and the major subcontractors to set goals and do the value engineering and the lifecycle cost analysis early on in the process would be beneficial. The goal is establishing procurement management procedures and getting our bid packages together early. But again, all with the understanding that it will be difficult and expensive to make changes once those orders have been placed.

Contracts

About contracts, we often see owners that draft their contracts to attempt to shift risk to the design professional. Sometimes this results in liability assumed in the contract that exceeds the legal liability of the design professional, which is for damages to the extent caused by failure to meet the professional standard of care. This creates a potential coverage issue because every professional liability policy has an exclusion for liability assumed under the contract that would not exist in the absence of the contract.

It is in nobody’s best interest to have an uninsurable agreement – especially the owner. Owners often miss this point and lose sight that a design professional’s PL insurance is third-party coverage – meaning that this coverage is for the client. Couple this with the fact that the average design firm has few liquid assets other than their insurance policies, and one has to wonder why the owner would want an uninsurable agreement. Unfortunately, this doesn’t stop the flow of onerous and uninsurable agreements that design firms must address.

Contractual liability issues usually flow from an increase in the professional standard of care, an assumption of the liability of others, or derogation of due process rights. We want to avoid agreeing to a “highest” or “national” standard of care or giving any guarantees or warranties regarding our service. So, their first priority is to establish an acceptable standard of care.

Assumption of the liability of others usually occurs in the indemnification clause. The duty to defend is probably the leading cause of pain here. Owners’ attorneys often need help understanding or appreciating the difference in responsibilities between design professionals and contractors. And they certainly need to understand the differences in insurance coverage. They are used to dealing with contractors whose obligations are related to general negligence and who can add additional insureds to their primary insurance policy, the general liability policy. Additional insureds will secure a defense for covered claims, so contractors agree to defend their clients from third-party claims. In jurisdictions subject to the economic loss rule, design professionals only owe a duty to their clients for purely economic loss, which is the primary type of claim made against design professionals.

Because we can’t add additional insureds to professional liability policies, there’s no defense obligation coverage relative to a professional liability claim. If the owner insists on a defense obligation, the best solution is a bifurcated indemnity. For claims-based professional liability, we will indemnify the owner, its officers, and employees for claims to the extent caused by our negligence. But we will not defend any of them.

For claims covered by general liability insurance, we can indemnify and defend the owner and other designated parties for damages to the extent caused by our negligence, under additional insured status. This bifurcated approach should satisfy the owner and preserve the insurance coverage available to the design professional.

Due process is implicated in any clause allowing the owner to withhold payment from the design professional without adjudicating that the design firm is liable.

Another contracting trend is indemnification for copyright infringement. This is troublesome because copyright infringement is typically alleged to be an intentional tort. Sometimes this is a bad act where a designer ripped off somebody else’s plans, but more commonly, it’s accidental. It occurs when a design professional has a dispute with the owner and the owner wants to take their plans and have somebody else finish them, or it’s an extension to an existing project. It’s not malicious. But we do not normally consider copyright infringement an error or omission. When we see these clauses, we try to revise them to reflect indemnification for negligent copyright infringement to bring that within the scope of professional liability coverage. This exposure can be managed by always creating original plans. The exposure increases if you are asked to finish a design that was started by another firm or when you are asked to match the appearance or style of existing buildings.

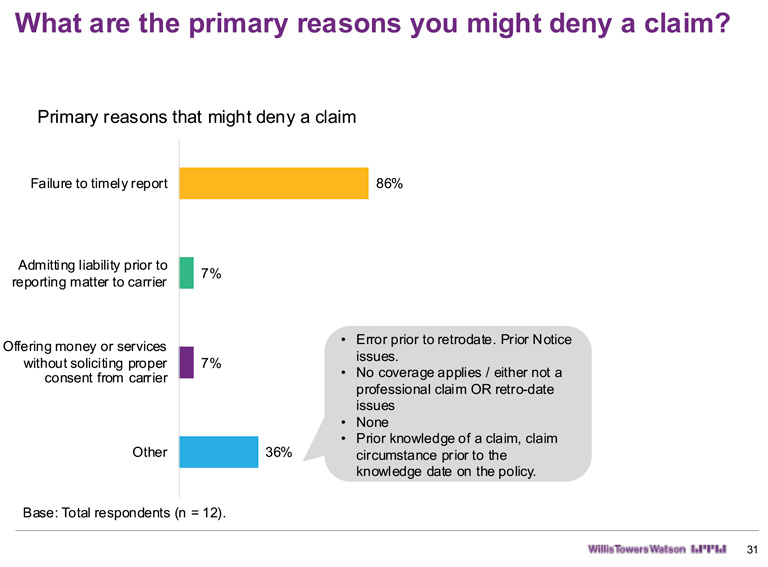

In the third and final article of this series, we will discuss the enhanced risks associated with certain project types, the most important thing you can do to preserve your professional liability coverage, and the state of the professional liability marketplace.■