Louisiana, Missouri Bridge 1873

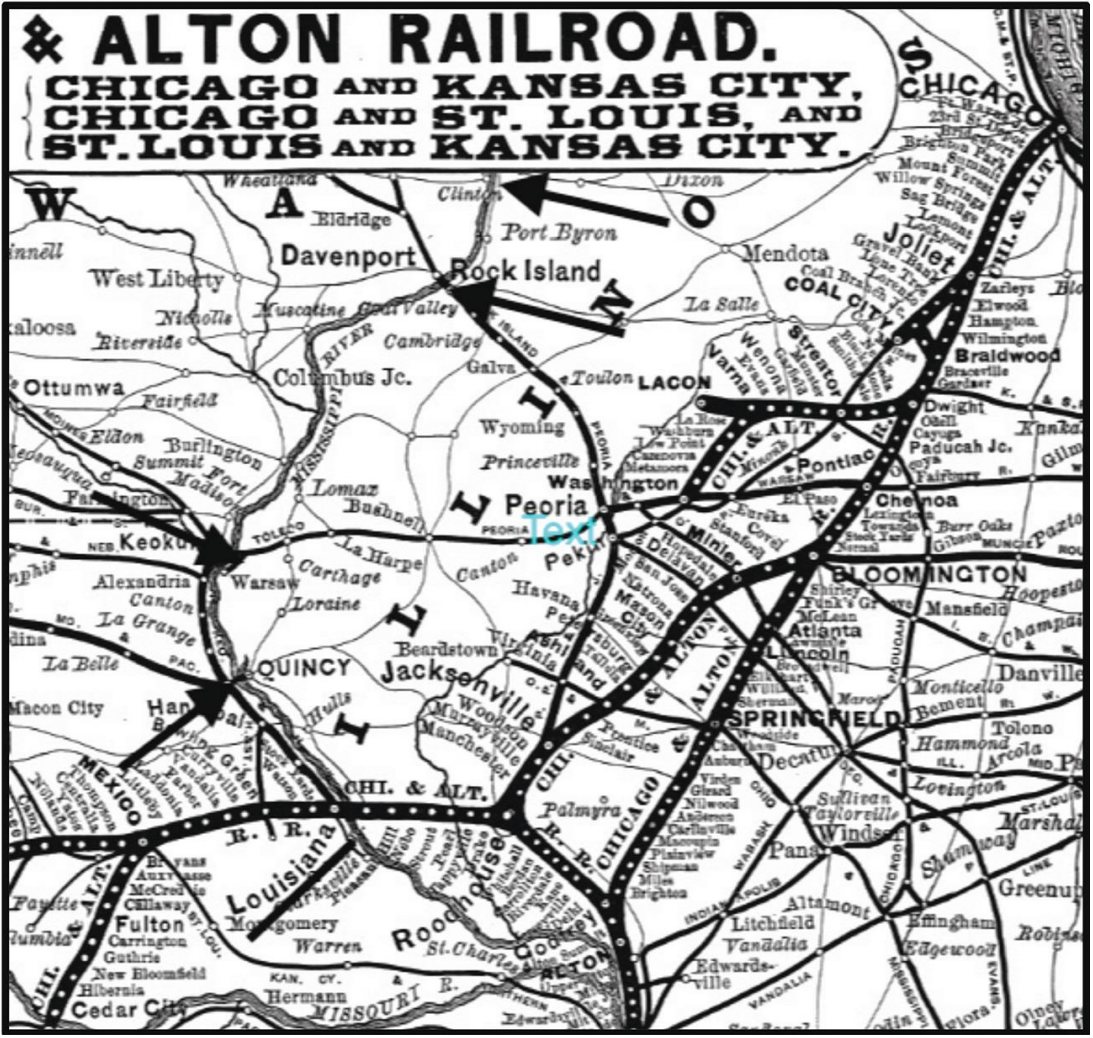

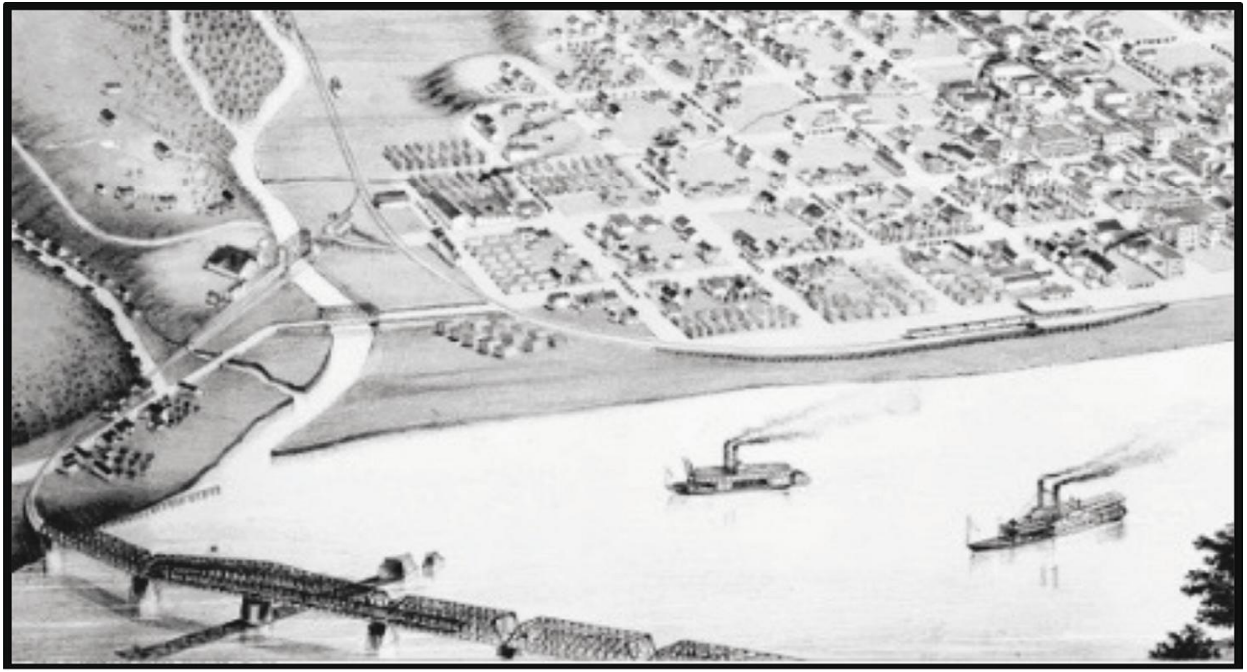

The Chicago & Alton Railroad was formed in 1862 to run from Chicago on Lake Michigan southerly to Alton on the Mississippi River. Over time a branch line from Bloomington to Roodhouse and then to the Mississippi opposite Louisiana, Missouri was built. From Louisiana west it had a line to Mexico, Louisiana and Jefferson City as well as a line to Kansas City. It used a car ferry for a period but needed a bridge across the Mississippi River to connect these lines. The site of the bridge was described as, “The general features of the river and surrounding country are a sandy bed, a bold rock bluff on the west near the river, a wide alluvial bottom on the east, rock appearing on the surface at the west shore, and a gradual slope to the east shore, where it is one hundred feet below the river bed. The width of the river on the bridge line is 3,900 feet.”

On February 15, 1871 the House approved the bridge and on March 3, 1871 the Senate followed suit. It was entitled “An Act to Authorize the construction of a bridge over the Mississippi River at Louisiana, Missouri, and also a bridge over the Missouri River at Glasgow in said state.” Unlike the July 25, 1866 Act that approved bridges across the Mississippi requiring for a low level bridge the clear space on either side of the swing pier of 160’, they upped it to 200’ clear stating “Provided, That if said bridge shall be constructed as a drawbridge, the same shall be constructed with spans of not less than two hundred feet in length in the clear on each side of the central or pivot pier of the draw.” This increased the length of the swing span from around 360’ to 440’. In addition, if a fixed high level span was selected it raised the clearance to 50’ above high water and all fixed spans over the main channel had to be a minimum of 350’ span. These increases were to pacify the shipping interests who were still against any bridge in the channel that would hinder their free passage.

On April 4,1873 a charter was granted by the State of Illinois and on April 9, 1873 a charter was given by the state of Missouri. On April 25, 1873 the two entities were combined with the Railroad Gazette reporting on May 31, 1873, “Articles of consolidation between the Mississippi River Bridge Company, an Illinois corporation, and the Louisiana Bridge Company, a Missouri corporation, have been filed with the Secretary of State of Illinois. The title of the new company is the Mississippi River Bridge Company, and the bridge which it is building is at Louisiana, Mo., for the Chicago & Alton road.”

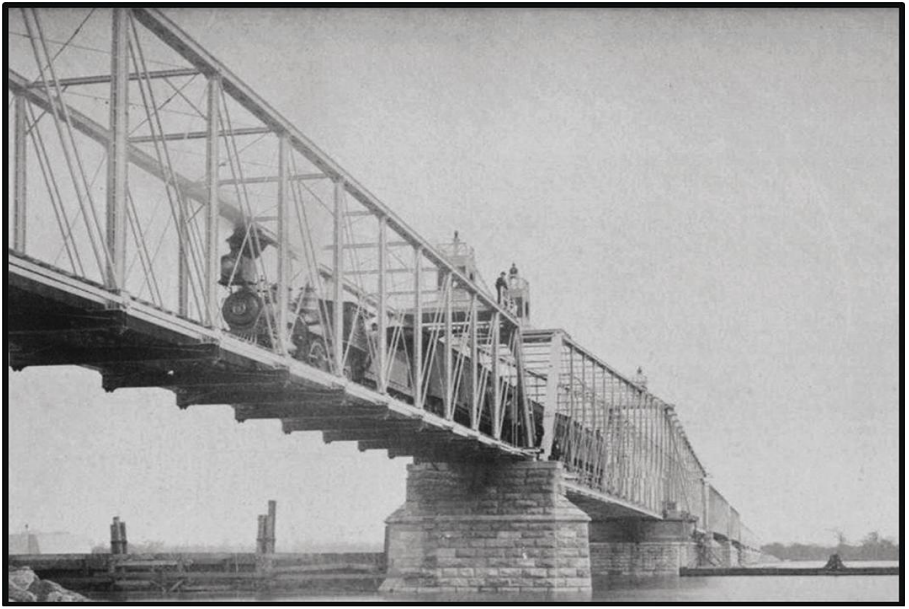

With the legalities out of the way in the late spring of 1873 the company decided to proceed with the bridge and received the approval of their plans from the War Department. The plan consisted of from west (Missouri) to east (Illinois), an embankment 2,800’ long; followed by spans of 160’, a 444’ swing span, a 255’ fixed span; a 223’ fixed span and six spans of 160’. The embankment on the east approach was 2,200’ long. They determined they wanted the bridge built before the year was out before the ice closed the river. They, Mississippi River Bridge Company, selected Elmer Corthell as their Chief Engineer. Corthell would go on to become a leader of the profession working closely with George S. Morison and James B. Eads.

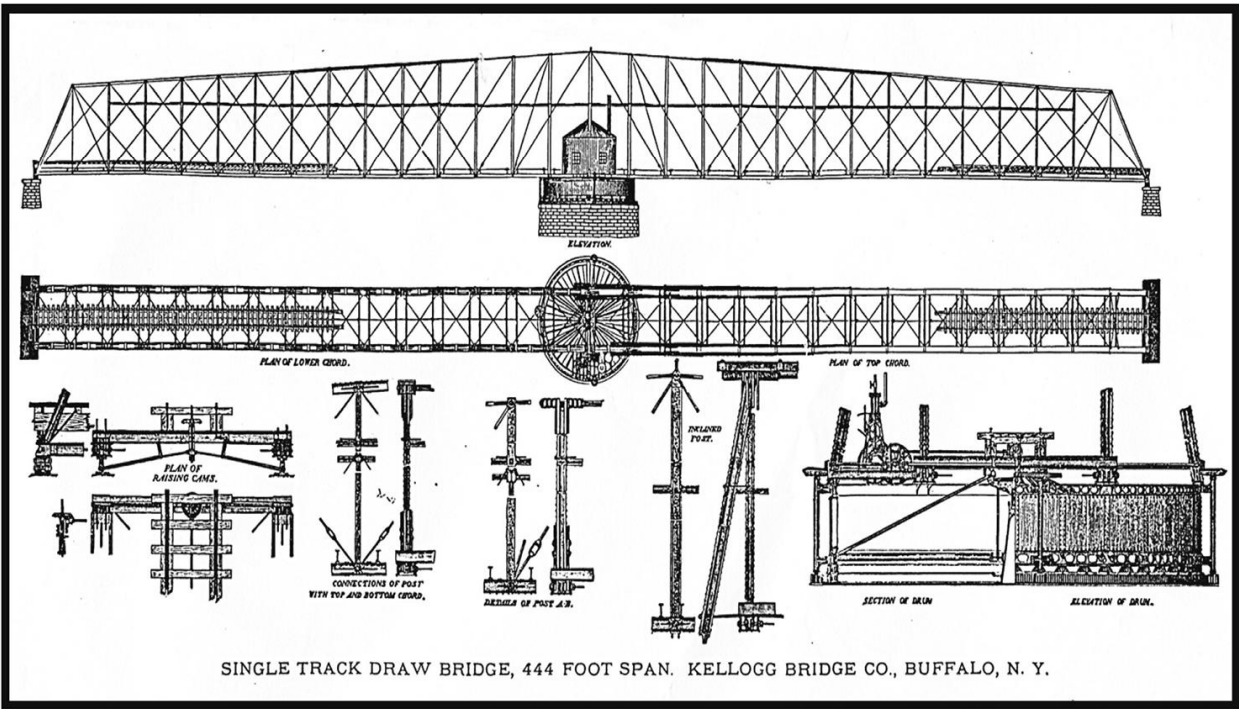

The masonry piers were built on wooden piles by Reynolds & Saulpaugh of Rock Island for $250,000. The same firm also placed the approach embankments. They had previously worked on several of the earlier Mississippi River bridges. To speed up the process the Company awarded the contract for the superstructure to three different bridge companies. The American Bridge Company built the 140’ span using a Post Truss. The Keystone Bridge Company, under Jacob H. Linville, built the six 160’ standard Keystone Bridge spans and the Kellogg Bridge Company of Buffalo, New York built the 444’ long swing span and the 255’ and 223’ spans, both Pratt Trusses. Charles Kellogg had been with the Detroit Bridge Company when they built the Quincy Bridge and with Kellogg & Clarke when they built the Keokuk Bridge. He started his own firm in Buffalo in 1870.

The river was known to shift its main channel over time. In order to ensure the main channel remained under the swing span they chose to build embankments to confine the river and a deflecting dyke upstream to guide the water. The confinement was accomplished by rip-rapped embankments extending into the river 550’ on the west side and 1,260’ on the east side. The report on the bridge noted, “The results obtained thus far are a quickening of the current between the dyke and the levee at Louisiana, the washing away of the bar below the dykes, and a deposit to some extent behind the dyke. The changes on the Upper Mississippi are necessarily slow, but it is confidently expected that this dyke, together with the embankment at the bridge line, will greatly improve the channel between the levee and the bridge, and hold it in its proper place through the draw.”

The major span was the 444’ swing span that was much longer than any swing span in the world at the time. The masonry for the pier was supported on 200 piles and contained 1,200 cubic yards of stone. The superstructure was a Whipple double intersection truss with sloping upper chords, 28’ high at the end and 39’ 8” at the peak, and was all of wrought iron. The trusses were 18’ on center. Surprisingly the total weight of the swing span was only 750,000#. The turntable had a diameter of 36’ and rolled on 48 cast iron wheels on a planed surface. It was said, “One man can move the draw with an ordinary hand-gearing, but it is worked by a double-cylinder engine. At the ends of the draw are cams for raising the ends of the truss on the draw-rest pier. These cams are worked by the engine on the turntable.” The 11th Annual Report of the line stated, “although a steam engine is provided for operating it, so perfect is its construction, that except when high winds prevail, one man can, without the aid of steam, open and close it.”

The entire length of the bridge was 2,052’ and the entire cost of bridge and river work was $685,000. A report by the Assistant Engineer, H. W. Parkhurst, that was published in the Railroad Gazette on January 17, 1874 noted, “The third peculiar feature of the work is the unusually short time consumed in the construction of the bridge. When on the 30th day of June last the instructions were given to have the bridge ready for business by Christmas, but few believed it possible to do it; but by planning the work to allow a margin for delays, by putting on a force commensurate with the work and the time in which it was to be done, with favorable weather and reliable and energetic contractors, the work has been done on time. The bridge was formally opened on the 24th of December, and since then all trains have crossed on the bridge.”

The bridge was rebuilt on the same piers in 1898 by the Lassig Bridge and Iron Works of Chicago. Several spans were replaced in 1945 and the bridge is now a part of the Kansas City Southern Railroad.■