19th Century Mississippi River Bridges Series

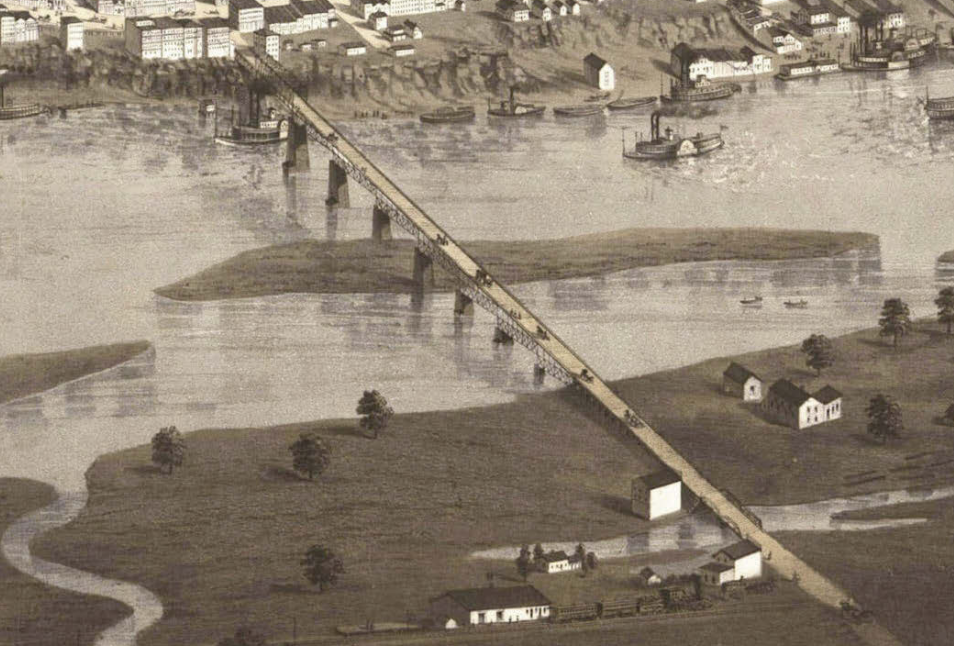

St. Paul, originally called Pig’s Eye, was founded approximately 13 miles downriver from Minneapolis near Fort Snelling. It was the northernmost access on the navigable river for steamboats on the Mississippi. It was settled on the north (east) bank of the Mississippi, on a bluff overlooking the river with low lands to the south (west bank). In 1849, the city was incorporated, and steamboat landings increased rapidly in the early 1850s. Its population reached almost 5,000 people by 1850. The river at the site was divided by Raspberry Island. Passage across the river was by rope ferries, and it soon became apparent that a bridge was necessary if the city continued to grow. As early as 1849, pressure to build a bridge started, and, in 1854, the Territorial Legislature passed Chapter 30, An Act to Incorporate the Saint Paul Bridge Company, on March 4. Sections 12, 14, 15, and 18 stated in part:

Section 12. Said bridge shall be of such material as the stockholders may deem expedient and shall be so constructed as to cover the main navigable channel of the river by a span of at least three hundred feet from pier to pier, the lowest part of which said span shall be at least sixty feet above high water mark – and said company may construct such other abutments, piers, and guards to said bridge, at such distances from each other and at such places as may be deemed necessary either on the street from which said bridge shall lead, on the island opposite said street, in the said river, or on the mainland on the opposite side of the said river. Provided that nothing in this section shall be so construed as to warrant the obstruction of any public street or the navigable channel of said river.

Section 14. No other bridge shall be established within one mile of that erected by the St. Paul Bridge Company without the consent of said company for the period of thirty-five years from the completion of said bridge.

Section 15. The said bridge shall, after the period of thirty-five years, become the joint property of the Counties of Ramsey and Dakota and shall thereafter be a free bridge.

Section 18. Set the tolls at: “For each foot passenger, ten cents; for each horse, mare, or mule, or two ox team, loaded or unloaded with driver, twenty-five cents; for each single horse carriage, twenty-five cents; for each additional cow or ox, ten cents; for each swine or sheep, two cents.”

The question was, as usual, what kind of bridge and who would build it. The requirement that there be a vertical clearance of 60 feet and a horizontal clearance of 300 feet to provide for the safe passage of steamboats theoretically set the location and elevation of the abutment and piers closest to St. Paul. From there, the bridge would slope down on bridge spans or filled land until it reached grade on the southerly end. The maximum slope was set by the load a team of horses could pull a wagon up a slope which was generally around 7%. This would set the line and grade. Given the low population and projected tolls, a low-cost bridge was necessary, which pointed to a wooden bridge. The bridge company selected J. S. Sewall as its engineer in June 1856. Sewall was born in Boston in 1827 and worked on several railroads between 1850 and 1854 when he settled in St. Paul, where he was a respected engineer and surveyor. However, there is no record of his involvement in the design of bridges.

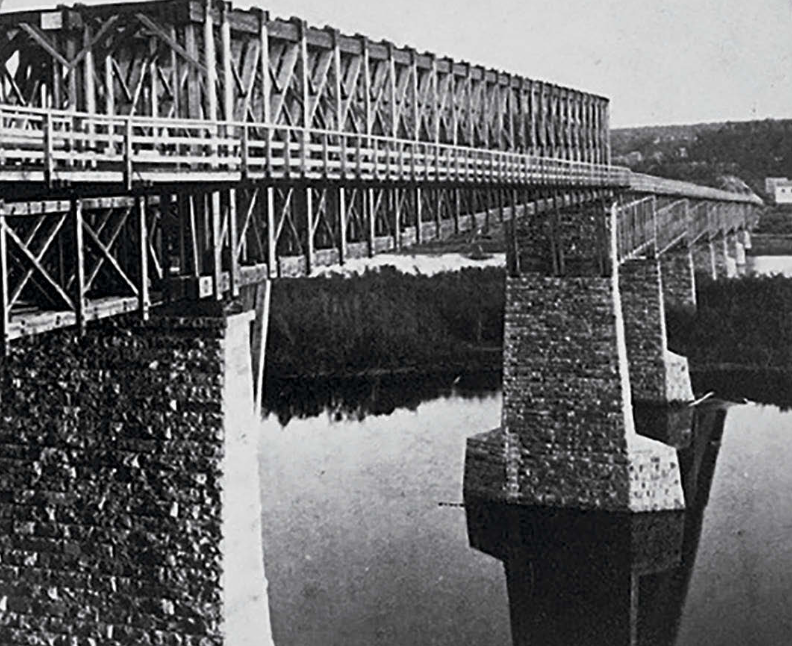

The most challenging design was for the main channel bridge that, by the enabling act, had to have a clear passage of 300 feet, but the company sought to decrease this to 220 feet. After the city council and steamboat operators claimed that this clearance would interfere with the safe passage of the steamboats, they agreed to increase it to 240 feet center-to-center of supports. They had already begun the construction of the far pier, so they had to move the first river pier 20 feet closer to shore. With the spans set, Sewall chose to use three lines of trussing with his compression diagonals spanning two panels, similar to William Howe’s design but with wood verticals instead of iron bars as used in the Rock Island Bridge (STRUCTURE, July 2022). In addition, rather than having his deck set on the lower or upper chords, as was the standard, he set variable distances up the verticals to provide a deck slope similar to his shorter spans.

His first span was a horizontal deck truss followed by the main channel span. The spans from the end of the channel span were parallel chord deck trusses of 140-foot-span set horizontal with wooden posts of variable heights and beams set on the upper chords to provide a sloping deck. There were seven of these spans down to grade. This was followed by a 330-foot-long wooden trestle to grade and a short bridge across a slough.

Sewall designed the foundations and stonework. In the summer of 1856, he advertised with a notice to contractors, The foundations will be piled. The timber required for the foundations will be furnished by the Company. The masonry must be bid for by the cubic yard, the foundations per pile, and per cubic foot for the cribwork. For further information, inquire at the office of the subscriber, where plans and specifications may be seen.

The contractor for the stonework was Rudolph H. Fitz of St. Paul, and the woodwork by J. & J. Napier also of St. Paul.

Wooden false works were required of various heights to erect the wooden spans, with the highest being over the main channel. Work on the piers was continued in 1857, but with stock sales slowing, the bridge company went to the city to purchase the remaining stock. The city agreed and sold bonds assuming bridge tolls would guarantee their investment. In 1858, Minnesota was admitted to the Union as the 38th State, and St. Paul was designated the Capital of the State.

As built from north to south, the spans were a 100-foot deck span, the 240-foot truss with sloping deck, and seven 140-foot spans with a similar slope to the main span. There were two lanes between the trusses with a total deck width of 17 feet and two 7-foot sidewalks.

The bridge opened in June 1859 at the cost of $161,855, of which the city of St. Paul contributed $114,870. However, tolls were far below the projected amounts, and the city took complete control of the bridge in 1867.

By 1869, the main span was showing signs of decay. It was replaced by a Howe truss with iron verticals in 1870. Shortly after, the seven sloping spans were replaced. In 1875, the main span was again showing signs of decay, and Soulerin and James Company erected a Whipple Iron Truss from Milwaukee, opening in July 1876.

This, the third bridge across the Mississippi, was built of untreated timber, which, uncovered, had a life expectancy of 10 to 12 years. Pictorial evidence exists that the upper chords of the main span were covered with little roofs for a part of the life of the span. It was replaced in 1890 with iron trusses erected as cantilevers and again in 1998 with concrete segmental box girder spans.

The Wabasha Street Bridge was the first to be built with a set of vertical and horizontal clearances to not interfere with steamboat traffic. However, this battle between steamboat captains and bridge builders over the right of free, unencumbered passage on the nation’s rivers would not be initially settled until 1866, when the Federal Government passed legislation governing horizontal and vertical clearances for high-level and low-level bridges with swing spans.■