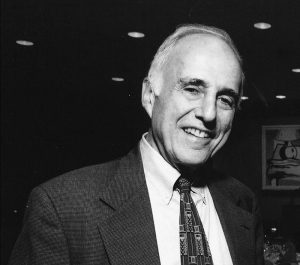

Robert (Bob) Silman, founder and President Emeritus of the structural engineering firm Silman, formerly Robert Silman Associates, passed away in 2018. Prior to the firm’s founding in 1966, Bob worked at Severud Associates, Ove Arup & Partners, and Amman & Whitney. Bob taught at Cornell, Columbia, Yale, and Harvard and was a fellow of the American Society of Civil Engineers. He was also an honorary member of the AIA New York Chapter, the Structural Engineers Association of New York, and the International Association for Bridge and Structural Engineering.

What always inspired me about having Bob as a boss was how deeply and admirably human he was at all times. He was an incredible schmoozer but never exuded sleazy salesmanship. He could talk about classical music and art, but in a way that drew you in if you were less learned, without him coming off as snooty. He was sharp with engineering insight but never pretentious about knowing more than someone else, even an entry engineer or layperson. He was a patient listener and a patient explainer.

Below are selections from his “notes to the firm” posts on the company intranet, which serve as excellent advice to any structural engineer:

Be Safe On-Site

During my first year of practice, when this was a one-person firm, I received a call on a very cold wintry morning. A piece of cast iron cornice had fallen from the 10th floor of the Ethical Culture School on Central Park West [and 63rd street]. Could I come out immediately? They had a scaffold on the premises because they were doing façade work at the time.

I was dressed in a business suit, an overcoat, leather-soled shoes, and gloves. So that is how I appeared on site.

The scaffold was a three-person maximum, 16-foot-long wooden plank scaffold, supported by hemp lines at each end that were manually hauled to raise and lower the scaffold. There was a “safety” arrangement consisting of a web belt tied off to the scaffold rail with a spare piece of light rope. No independent safety lines, no toe board, a thin film of ice on the planks of the scaffold! I climbed through the top floor window to access the scaffold, and as my leather-soled shoe hit the ice, I started to fly out into Central Park as I had not yet attached the safety belt. One of the mechanics grabbed me and laughed.

Upon returning to the office, I went out and immediately bought a pair of stout, Vibram-soled shoes at a significant cost (Vibram soles at that time could be had only on costly imported Italian hiking and walking shoes). I still have these Fabiano shoes, and they work well. I then kept a set of appropriate clothing for site visits stored in the office that I could change into on short notice.

What a far cry from today – motorized scaffold on steel wire suspension, full harness arrest system clipped to an independent safety line, toe board, grating floors that do not ice up, railing with intermediate horizontals, and most of all – training and certification required before you can even go out on a scaffold.

Not such fond memories of the old days.

Use Technology with Caution

We are a firm of technologists. We call ourselves structural engineers, and, by definition, that makes us proponents of technology. Most of us take it for granted that if we are at the leading edge of the uses of technology, we are doing the best thing possible. That is what progress is all about, and who can argue that “progress is our most important product” (that was General Electric Company’s slogan for many years).

Perhaps we should distance ourselves for a moment from what we are embroiled in every day. Perhaps we should consider whether modern technology is different from the erstwhile technology that has allowed us to arrive at our present stage of development. Many of you know that I teach the Philosophy of Technology course at the Graduate School of Design at Harvard. One of the philosophers that we read, Hans Jonas, points out that there are many dramatic differences in contemporary technology compared to what has gone before. Most importantly, the results of earlier technologies were proximate. We could see all of the results almost immediately.

Today’s technologies sometimes result in consequences that we could never have dreamed of, occurring far down the road, maybe long after we are gone. Many of these result in environmental degradation or serious health consequences. The push for sustainability and green design in our buildings addresses some of these issues. But the suggestions of sustainability advocates address the known. What about the unknown? I would like to suggest that each of us seriously consider what we are designing and drawing. Will it possibly result in unknown future consequences? Will we be guilty of the next DDT debacle? Maybe it is OK to use caution, think twice, or raise a yellow “go slow” flag before endorsing the next new thing. I am not advocating that we become Luddites, only that we consider the future.

Be Proactive

We talk about “being proactive” all the time, but what do we mean?

- Do not wait to be contacted, but initiate the contact yourself. If you need information to proceed with your work, ask for it immediately or, better still, anticipate what you will need and be sure you have it before you need it.

- Make lists and send them on to the client. If you know what you will require by when, talk to the client in advance about upcoming deadlines and when you can expect the information. Then once it has been decided upon, memorialize the conversation by writing it down in a friendly way and sending it on in the form of a list or a memo. That way, there is no misunderstanding. Clients easily forget what they have promised to send us when under pressures of their own.

- Do not allow long periods of silence to go by when working on a project. Even if you are in the midst of a long series of calculations that will have no meaning to the client until you have completed them, call them frequently to tell them what you are doing so that they do not think that you have forgotten them or are not working on the job. Put yourself in their place. Even if you are between phases or the project has been put on hold temporarily, contact the client regularly to check on the status; this shows our interest.

- Even if you are not working directly on a project with a client now, but you have had a good past relationship, call the former client every once in a while just to keep in touch. You would be amazed how far this goes.

- If you see or read something that may not pertain to the project directly but would be of interest to the client, send it along. Make sure that it is appropriate, however – nothing politically incorrect!

Whatever you do to be proactive, treat it gently. Do not come down like a hammer and make demands. Remember that part of our culture is to function with joy. Pass some of that along.

Own Up to Mistakes

Who of us never makes an error? It is said that the great Turkish rug makers always intentionally wove a small mistake into their pattern, saying, “Only God is Perfect.”

What should be our response as an individual in a firm when we find that we have made a mistake? The natural impulse is to cover it up if possible. Or blame it on circumstances beyond our control or on others. But most of us have learned that such actions come back to haunt us.

The only acceptable course of action is to own up to it as soon as we realize it. We must go to our immediate supervisor and discuss the whole thing in total candor. That does not mean that it must be broadcast through the PA system so that everyone knows! Then a decision has to be made as to how to handle the situation. Most rational people understand that others make mistakes, and they allow for it. That is generally thought to be why jobs carry a contingency during the construction phase, to allow for such mistakes or omissions. And it is said that the best way to learn is from our mistakes.

Personally, I once made a glaring design error during my first year of practice when I used the wrong method to design a 30-foot-high braced wall of steel sheeting…. The job was out to bid, and I had to go to the [client] and tell him that we had to recall the job, fix the error, and rebid the job. His response was, “Good that you found the error now. It’s no big deal to fix the drawings and rebid the job. Go to it.” And we got lots more work from that client. Had I tried to make excuses, I think that this particular person would have thrown me out. But he appreciated my honesty.

Go to your supervisor if you make a mistake, and together you can work out a strategy for fixing it. Don’t be afraid to be honest about it. We all make mistakes. Only God is perfect.

Broaden Your Horizons

As I think back over the years to the many mentoring sessions that I have participated in, there is a recurring theme. People ask me, “What should I do so that I can improve my performance or even ‘stand out’?” One area that is generally lacking is intellectualism. Without trying to be elitist or pedantic, or preachy, I would say that all of us can stretch our minds a little further every day in all kinds of ways that may not seem directly related to our job performance. Read a book that challenges you, that makes you think about what you just read, or perhaps requires you to go back and reread what you just read simply to understand it. Go to a museum, look at something you have never seen before, and then do some research on what you just encountered. Go to a performance where the milieu is a different one from what you usually encounter – classical music if you usually listen to rock, a play if you usually go to a movie, an opera if you’ve never been before, a lecture, a reading. These don’t have to cost a lot (or anything) if you go on a free night to the museum or go to a student performance.

We all know the benefits of exercising our bodies and stretching our muscles. How about our minds? It is amazing how much better you will feel. And without possibly noticing it, how much better you will perform your role at work.■