A Look at Preserving the Future of Structural Engineering

“If you like solving puzzles, this is a profession you can enjoy doing it and be paid for it. You build things that last a century. Much more rewarding than practice of Medicine and Law. And you can do this way past retirement and keep enjoying it.”

“Stay out of this career. Too many long hours, high stress and nobody cares… My wife hates me, and my kids don’t know me. Nobody should have to work this much in life. If it paid a lot of money, that’s one thing… but it doesn’t. If you’re considering structural engineering… you’re a bright individual… use your brain to do something else.”

Would you believe that these two statements came from people who share the same profession? Have you found yourself saying one of these things? Have you found yourself saying both of those things? Hopefully, if you’re reading this right now, you’re more aligned with the former statement than the latter. Now think about someone you know, maybe a classmate or a former colleague… someone who started out as a structural engineer only to one day decide they were leaving the profession. Most of us can think of one or two people that we’ve known over the years whose departure was a true loss to the profession.

So why did they leave?

Could something have been done different to prevent them from leaving?

These questions inspired the SEI Young Professionals Committee to look into the question of “why people stay” and “why people leave” as part of a series of topics on enhancing the future of structural engineering. To do this, a survey was mass emailed to people in the profession with the caveat to pass this along to their colleagues – both current and former. The survey questions were combined with another survey on diversity within the profession. In total, 741 people responded. Of those, 107 (14%) identified as not being practicing structural engineers.

The survey included demographic data, in terms of where they worked, how long they’ve worked, level of education, and what type of work they did. The survey was then divided, with questions for those who were still in the profession and those who had left. At the end of the survey there was an option to provide additional written comments. All of the quotations interspersed throughout this article are directly from the survey.

View of the Profession

“…the stress and demands of the job in today’s environment have increased considerably over the span of my career due to the requirements for tighter schedules and faster production combined with a fee structure that has basically remained unchanged for years.”

“The profession is becoming more of a commodity service. Another issue is that college graduates now are much less prepared to be productive, proficient engineers than they were 20 or 25 years ago.”

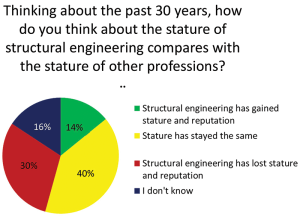

These statements represent two common themes voiced in publications and at conferences. Therefore, a reasonable place to look for why people are leaving the profession would lie in their perception of what they did. The survey asked responders for their opinion and the results were interesting. Responders, practicing and formerly practicing, said that they believe the profession has lost stature as opposed to gaining stature by a margin of 2:1. However, an equal number of responders said they believed that the stature has not changed.

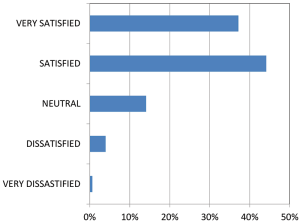

With a significant number of survey respondents indicating they felt the profession had lost stature, it was interesting to note the number of people who indicated they were satisfied with their current job. In the survey, only about 5% of the responders who were currently structural engineers indicated they were dissatisfied with their career. That is in stark contrast to the 80% who indicated they were satisfied or very satisfied with the profession.

Why They Leave

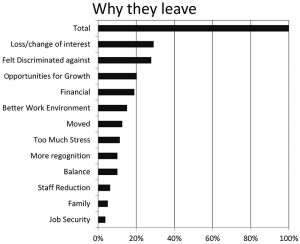

Examining the data on why people choose to leave the profession did not reveal any specific, overarching reason. The “Why They Leave” graphic highlights the most significant reasons identified by respondents. The numbers add to greater than 100% because some people identified more than one reason for why they chose to leave. The most significant reason people choose to leave is that they lose interest. Surprisingly, being discriminated against is a very close second. A perception of lack of growth opportunities and financial pressures were the next two items which contributed to people leaving.

The loss of interest or perceived lack of growth opportunities were tough to determine if they could have been prevented. On the one hand, every firm has its share of repetitive tasks and it can be easy for someone to get burnt out. However, it was clear from some of the survey’s written responses that many people felt like they were doing the same thing over and over, often at greater than 40 hours, without the recognition they felt they deserved. The following quotation harshly, but truthfully, describes one responder’s feelings.

“My job as a Structural Engineer has been much more conservative than I originally thought it would be. It feels like working in a retail job; responsibilities seem more tied to term than ability, and people seem afraid to give responsibility to young people. I believe this to be very consistent with other professions of high responsibility, but with a much lower long term salary potential.”

Regarding the financial reasons, so much has been written about this and talked about at professional conferences that an entire book could be written about it. However, one commenter summed things up rather well with the following,

“I love the technical aspects of our field and the satisfaction of seeing something I designed built. However, the business practices within the field are extremely frustrating. I have had many friends leave the profession to pursue other professions where they work the same amount but make much more money. I worry that we have a long term issue with attracting, compensating, and retaining talent. I believe a key problem is that many of the people running firms have little to no business training. We lament that we can’t make money, yet when it comes time to negotiate a fee we don’t think about how much effort we will have to expend and the scope, but instead use a number that we think will get us the job. We also have contracts with poorly defined scope that lead to “scope creep” and doing work for free. Yet we then wonder why we lose money. Also, there is a willingness within the field to ‘buy work’. We also are not trained to communicate. This leads to difficulty in communicating the value we bring to owner which then leads to selections based solely on fee. While technical training is key to engineering education, we are professionals – not technicians. Most engineers eventually (and sometimes quickly) rise to a level where we are managing younger engineers, marketing our services, and negotiating contracts. However, we receive very little training in those areas.”

The fact that feeling discriminated against was the reason for almost 30% of the people leaving the profession was surprising, and frankly shocking. With a profession that has a significant underrepresentation of women and minorities (Liel, STRUCTURE® magazine, October 2014), this is an issue that should be looked at in more detail.

Several of the reasons people left the profession were outside of their control, such as moving, family issues, or being part of a staff reduction. However, the numbers who indicated that was the reason they left was small compared to those who lost interest, felt discriminated, didn’t see growth or wanted more money.

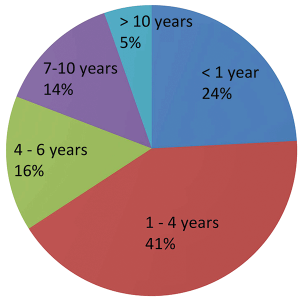

The survey indicated that most people who leave the profession do so within the first five years of beginning work, with almost one quarter leaving within their first year.

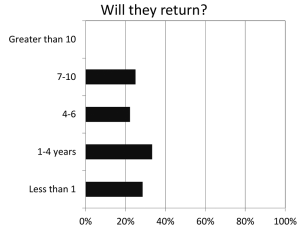

With so many people leaving the profession so early, a natural question arose of whether they could come back into the profession. Of those surveyed, less than 30% indicated they would return. The numbers remained somewhat constant up to those who had been out of the profession for more than 10 years. It is noteworthy that there is a possibility for people to return; however, no respondents indicated they had left the profession and returned.

This is significant. Our profession does not lend itself to people making a mid-career change into it. Any mid-career change would involve significant coursework at the undergraduate level and possibly a master’s degree.

A Case for Mentorship

“I think the availability of a mentor is important to the development of an engineer in any field. It is something I wish I had sought more.”

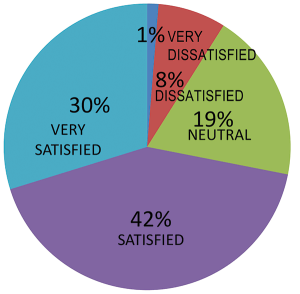

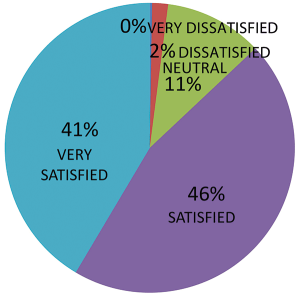

One bright spot within the survey was the very apparent positive influence of mentorship. The two pie charts on mentorship show satisfaction ratings for those who did not identify as having any mentor versus those who did. Satisfaction increases from around 70% to almost 90%. More importantly, dissatisfaction drops from 9% to 2%.

Considering the two most significant reasons people left were losing interest and feeling discriminated against, mentorship appears to be a significant way to address those issues. Anecdotally, it seems that having a mentor can go a long way toward keeping someone engaged and feeling their contributions are meaningful. It also appeared that a mentor could help one to address discrimination within their organization. Thus, the importance of mentorship cannot be understated in improving retention rates.

Conclusions & Actions

Now that the economy is starting to recover and job opportunities are becoming more prevalent, think about what your firm can do about retaining the people you’d like to retain. What can be done to keep your people engaged?

Mentorship is key to retention. You are never too young to take on a mentee. The effects of mentorship are apparent and appear to lead to significant increases in job satisfaction and retention. If you don’t feel you can find one within your oganization, look to local and national professional socieities. Many respondants replied that they found a greater degree of engagement and mentorship through their involvement in a professional organization.

It appears from the survey that the we need to take more steps toward ending discrimination. The fact that almost 30% of those who left cited feeling discrimiated against is alarming and unacceptable. Examine your organization’s culture and why people have left. Is this something that needs additional attention within your company?

Lastly, inspire someone in your company or your professional organization to feel like this person…

“[Structural Engineering] is a rewarding profession where you see tangible results for your work with the construction of something. You can feel fulfilled in your day and have meaning to your work life this way.”▪

All graphics courtesy of ASCE.