Structural Engineering Engagement and Equity (SE3) Committee Survey Results

Results of the 2016 SE3 Study discussed in Part 1 (STRUCTURE, April 2017) focused on overall career satisfaction, development, and advancement. Part 2 of this series (STRUCTURE, August 2017) focused on compensation, overtime, and the gender pay gap. This article highlights the survey findings regarding work-life balance, flexibility benefits, and caregiving. A full report that includes all the findings discussed in this series can be found at SE3project.org/full-report.

Work-Life Balance

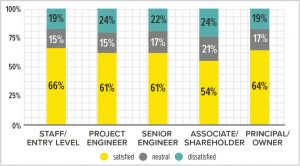

“Work-life balance” is a popular phrase in modern discussions of employment and engagement. Research, articles, and ongoing studies attempt to address common concerns arising from an imbalance between the time spent at work and the time spent outside of work attending to other “life” interests or tasks, such as exercise, hobbies, errands, and care of children or dependents. Twenty-two percent of the respondents to the 2016 SE3 survey reported being either dissatisfied or very dissatisfied with their work-life balance (Figure 1 shows this breakdown by position). Poor work-life balance was also one of the top reasons that respondents considered leaving the profession and one of the leading reasons that respondents reported leaving the profession.

Flexibility Benefits

In the past several decades, more women have been entering the workforce globally. In 1950, women comprised approximately 30% of the U.S. workforce; today they comprise nearly half (The Council of Economic Advisers, 2014). As women used to commonly be primary caregivers to children, this change in the number of women in the workforce makes raising children more difficult for parents who are often now both employed outside the home. (Eldercare is similarly difficult; nearly two-thirds of people providing unpaid elder care have jobs, and about half of caregivers work full-time.) This evolution of family life requires a new corporate culture that accommodates the needs of working parents.

Although having children or dependents is common (51% of respondents have children or dependents), survey findings indicate a stigma associated with employees who care for children. Even though many firms now offer “flexibility benefits,” such as flexible work schedules, maternity/paternity leave, reduced hours, and the ability to work from home, many individuals are hesitant to take advantage of these benefits. Additionally, only 19% of respondents had taken time off from their structural engineering careers, with maternity/paternity/parental leave identified as the primary reason.

Some respondents are indifferent to coworkers using flexibility benefits, but others expressed criticism of their peers who choose to use them. Reasons indicated included a perceived reduction of productivity, decreased motivation, decreased accountability to clients, and significant inconvenience to other staff, the last of which is the most commonly cited complaint regarding those who either work remotely or have reduced schedules. Twenty-two percent of the respondents who do not have children or dependents indicated that they were sometimes left to “pick up the slack” for their coworkers with children or dependents. Thirty percent of the respondents reported that they feel they work harder than their peers with children, and 30% of the respondents also reported that their managers expect them to work more hours because they do not have children.

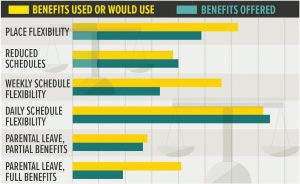

Of the benefit options surveyed, respondents indicated that a flexible daily work schedule is the benefit most commonly offered by employers and the most widely used. Over 70% of the respondents stated that their company offers flexible daily work schedules, and nearly the same number reported that they use or would use this benefit if it were offered, as shown in Figure 2.

The biggest discrepancies in benefits that were offered versus those that were used or desired were weekly schedule flexibility and parental leave with full benefits. Only about one-third of the respondents’ employers offer weekly schedule flexibility (e.g., working four ten-hour days instead of five eight-hour days). In comparison, more than half of the respondents said they have used or would use this benefit if it were offered. Nineteen percent of the respondents reported that their companies offer parental leave with full benefits (paid maternity or paternity leave after having a child), while 41% of the respondents indicated that they have used or would use this benefit if it were offered.

Findings from this survey align with other recent discourse that suggests that modern corporate culture in the United States generally does not embrace the needs of caregivers by allowing them to tend to both family and work obligations (Slaughter, 2015). While many companies offer flexibility benefits, they are often negotiated on a person-by-person basis and not well supported by management or other staff. Studies show, however, that increased flexibility benefits can help alleviate employee stress about balancing family with work and can result in improved employee happiness, health, loyalty, and productivity (The Council of Economic Advisers, 2014). Another recent study reports on a systematic management approach that can be used to more effectively manage flexibility needs without burdening non-caregivers with additional workload (Fondas, 2014).

Advancement of Respondents with Children

Respondents with children reported advancing at a slower rate than those without children, regardless of gender. On average, it took respondents without children 8.5 years to reach the senior engineer/project manager level, 11.6 years to reach the associate/shareholder level, and 14.7 years to reach principal/owner. It took respondents with children 11.5 years, 13.7 years, and 14.9 years, respectively, to reach those positions, as shown in Figure 3.

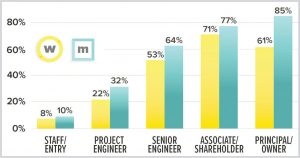

At every position level, female respondents were less likely than male respondents to have child dependents, which may contribute to the finding that female respondents reach each level of employment except principal/owner more quickly than male respondents (as discussed in the Career Development section of the 2016 SE3 Survey Report). At the principal/owner level, 85% of male respondents reported having children, compared to only 61% of females, as shown in Figure 4.

Despite the difficulties reported, the respondents with children reported higher overall satisfaction with their career than those without children.

Caregiving Responsibilities

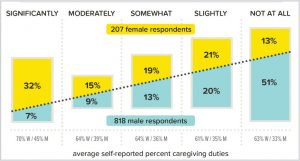

When asked to estimate the percent that they contribute to caregiving responsibilities, on average women responded that they contribute 65%, while men reported that they contribute 35%. Women were also significantly more likely to feel that having children has affected their career. In fact, for both genders, as an employee’s percent of caregiving responsibilities increased, so did his or her feeling that children had affected his or her career, as shown in Figure 5. Because more men are taking on a larger percentage of caregiving responsibilities compared to previous generations, this issue no longer applies only to women.

As the percentage of caregiving increased, respondents were more likely to report a decrease in motivation and productivity. For the 192 respondents who reported having more than 50% of the caregiving responsibilities in their family, 22% reported a decrease in motivation at work after having children, and 21% reported a reduction in productivity. In comparison, of the 563 respondents who reported having less than 50% of the caregiving responsibilities, only 6% reported a decrease in motivation at work after having children, and 12% reported a decrease in productivity.

Loss of motivation and productivity was more concentrated in women, which correlates directly to the higher rate of caregiving responsibilities that women reported. When asked about work motivation after having children, 41% of men reported an increase in motivation, compared to only 21% of women, and only 7% of men reported decreased motivation, compared to 21% of women. When asked about work productivity as a working parent, 19% of women reported a decrease in work productivity relative to life without children or dependents, compared to 13% of men.

Looking at these factors together for women with children – a higher percentage of caregiving responsibilities, stigmas in the workplace against those who use flexibility benefits, and correspondingly less productivity and motivation after children – it is not surprising that women are less satisfied with work-life balance, which was reported as their top reason for considering leaving the structural engineering profession. It is also clear that better engagement of female engineers – or even engineers of all genders – depends heavily on changing the perception of the value of parenting. If employees feel supported in their work and life outside work and are allowed flexible schedules as needed to care for children and dependents, then perhaps they would engage better within the profession after transitioning into a working parent role and, in some cases, stay in the profession when they may have otherwise left.▪

References

The Council of Economic Advisers, 2014, Work-Life Balance and the Economics of Workplace Flexibil-ity, Executive Office of the President of the United States, Washington, D.C. Available at https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/docs/updated_workplace_flex_report_final_0.pdf, last accessed July 1, 2017.

Fondas, N., 2014, “Your Work-Life Balance Should Be Your Company’s Problem,” Harvard Business Review, June 10, 2014. Available at: https://hbr.org/2014/06/your-work-life-balance-should-be-your-companys-problem, last accessed July 1, 2017.

Slaughter, A.-M., 2015, “A Toxic Work World,” The New York Times, September 18, 2015. Available at: http://nyti.ms/1iCiBjz, last accessed July 1, 2017.